Truth, Kindness and the American Way: A Non-American Perspective on ‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’

We’ve grown to detest sincerity, haven’t we?

Or at the very least, we as a culture have grown suspicious of it. We have a need to see even the purest of kindness through a lens of the pain and suffering that drive it – friendly, neighborhood Paddington, like the friendly, neighborhood Spider-Man, was an orphan who subsequently lost his uncle – and we view kindness this way only if we aren’t first investigating the potential selfishness driving what we think is pretense. In either case, even fictional views on empathy and heroism, especially in American media, tend to focus on some kind of trauma. Captain America, who wears the star-spangled banner on his chest, lost everyone he ever loved before even waking up. Perhaps there is no such thing as kindness not born out of cruelty.

Perhaps there is no longer such a thing as American kindness detached from the various specters of September 11th; tragedy is a through-line for us all. Even the cinematic Superman, once a friend, has become a morose figure detached from humanity and the kindness of his “American way.” He was re-introduced to the world in Man of Steel amidst scenes of buildings crumbing into piles of ash, and his stories since have seen him wrestle with aloofness. Where would the citizens of Superman’s city, abandoned by their most reliable neighbor, have looked for the helpers, I wonder? Admittedly, I often wonder this about real American cities nowadays.

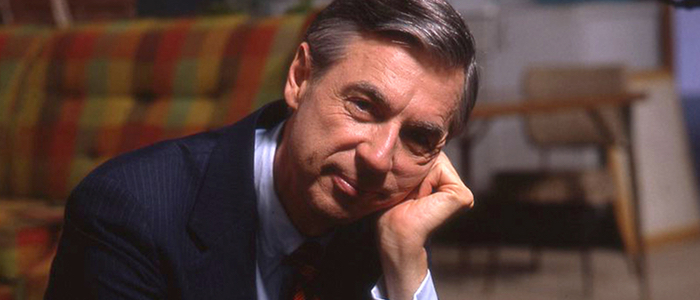

And that brings me to Fred Rogers and the new documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

Superman and Fred Rogers

Like most children outside America, I did not grow up with Mr. Rogers or his neighborhood. Global popular culture is largely American, though not all of it travels. My window into the kindness of the American heartland was in fact the Man of Tomorrow, Superman, whose red and blue I was familiar with from an early age and whose kindness seems almost uncanny today. Whether Christopher Reeve or Superman: The Animated Series or some statuette gifted to me by my grandmother, Superman felt like a symbol that may as well be described now as “old-world” naiveté. How can someone be so kind, so empathetic and so seemingly unselfish and still be an interesting character, let alone a real person? People ask this question of Superman just as they seem to ask it of Fred Rogers, a man who could not possibly remain the kindly American TV neighbor after the credits had rolled. Could he?

Morgan Neville’s Won’t You Be My Neighbor? hopes to respond to this looming curiosity, and the answer is…complicated. The film begins with a resounding ‘Yes’ – at first anyway. The polite cadence, the tone of understanding seemingly aimed at children, all continue behind the scenes. Neville’s documentary opens with Mr. Rogers attempting to welcome other adults, with open arms, into his philosophy of kindness despite not being able to fully express it. He mixes musical metaphors while playing his piano out of tune in order to demonstrate emotional fragility, and it’s simply delightful.

Fred McFeely Rogers, born 1928, may not have been able to articulate the value of an emotional education in anything approaching academic terms, but his awe-inspiring dedication to helping children feel seen spoke volumes all on its own. I don’t need to tell you this if you’re American, or grew up in America. If you didn’t, any American will tell you about Fred Rogers unprompted.

My friend and Entertainment Weekly writer Anthony Breznican has a story about meeting him in college – you may have read it – a tale indicative of the impact of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which ran off and on from 1968 to 2001, totaling 912 episodes over 31 seasons. Fred Rogers’ relationship to most Americans is crystal clear: he provided comfort and guidance to those who needed it. But what of his relationship to America itself?

American Dreams

Fred Rogers died just weeks before the invasion of Iraq. His show began several years into the Vietnam war, and during the program’s very first week, he used puppets to help American kids deal with ideas like armed conflict and building of border walls, which seemed too vast for a child’s mind to fully comprehend. Over the years, whether dealing with racial segregation or political assassination, he simplified the American experience in order to comfort the youngest of those affected by it. But the paradox therein – and there is always a paradox when it comes to America – is one the film unearths in all its complex hues.

After the turn of the millennium, as chronicled in the film, conservative criticism of Mr. Rogers twisted Neighborhood’s message into one of entitlement, rather than understanding. This very idea of entitlement tends to be the go-to of the American Right, a “Get Out of Engaging-with-issues Free” card that presumes neither history nor circumstance are relevant when levying complaints against a system. In the case of Mr. Rogers, the system he was trying to combat was the age-old wisdom that children should be seen and not heard – that their emotions, and thus their emotional development, required no nurturing or care.

Mr. Rogers cared, no doubt, and he got enough kids to care that the effect of his kindness still lingers, carried on in each of them as adults. But even Mr. Rogers was bound by his era, a paradox as potent as America itself, the “land of the free” founded on human enslavement and genocide, where “the American Dream” is shouted from rooftops, a dream shining brighter than any other the world over, but a place of dreams where the reality now seems grim. In many ways, it always has been.

The Tools We’re Given

François Scarborough Clemmons became the first recurring African American actor on children’s television, as the neighborhood’s Officer Clemmons. In an era where segregation still ran rampant despite having been struck down legally – the YMCA’s pools were still off-limits to Black children in 1969, a year after Clemmons joined the show – Rogers conceived of an episode wherein he and Clemmons would not only dip their feet in a pool together on a hot day, but Rogers would help Clemmons dry off with a towel. It was a loving and intimate gesture (one the duo repeated on the program in 1993 during their final episode together) and it flew in the face of the continued racism of the time. But Fred Rogers’ love was not without complications.

Clemmons was also a closeted gay man. While the Civil Rights movement had been going on for years, giving “allies” like Fred Rogers the opportunity to acclimate to specific struggles, Queer Pride was still in its infancy – the Stonewall riots took place only a month after the historical pool episode. Upon learning that Clemmons frequented a known gay bar, Rogers told him to keep his sexuality a secret. If word got out, the network would more than likely take Rogers’ show away from him. In short, he convinced Clemmons to help him continue his mission to help children, a mission that involved speaking out against certain forms of oppression, by adding to the decades of another kind of oppression faced by Clemmons.

Even in the Home of the Brave, fear turns progress into a tiered structure, where people have to wait their turn. American women’s suffragist Susan B. Anthony for instance, once an anti-slavery advocate, worked to prevent black men from being granted the vote before white women were granted the same. History is complicated, as are the people canonized in its pages. Fred Rogers was one such figure, a product of his time doing his very best with the tools he was given – but the miracle of Won’t You Be My Neighbor? isn’t just that it captures a heavenly kindness, but the evolution of a kind man’s understanding of the world, often in subtle ways.

Continue Reading Truth, Kindness and the American Way >>

The post Truth, Kindness and the American Way: A Non-American Perspective on ‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’ appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/2JliY3I

No comments: