It’s been over a week since I watched the Watchmen episode, “This Extraordinary Being.” I’m glad I took that time to digest what I watched before I sat down to write this piece, because this episode is, without a doubt, one of the best television episodes of this year. Maybe the entire decade. How writers Cord Jefferson and Damon Lindelof crammed that much social commentary and emotional power into one hour is beyond me. Congrats to the writing team for achieving the same level of impossibility and layers of social context that the original Watchmen text achieved in its day.

What was so great about this episode, you might be asking? Well, frankly, it’s hard to know where to begin breaking down the various levels this episode was speaking on. However, I’ll start with this: I highly recommend you read multiple people’s takes on this episode, especially Black writers. Not all Black writers think the same, and we’re bound to find different things from this episode to speak to.

This post contains spoilers for Watchmen.

The relatable impossibility of Hooded Justice

Without spoiling myself too much, I read the headline of a Hollywood Reporter article that came to me in my email. Through that headline, I learned that Hooded Justice was going to be revealed in this episode and I set my mind to try to figure out who he could be. I went through nearly impossible theory I could think of, from Dr. Manhattan possibly becoming two people to Police Chief Judd Crawford being Hooded Justice despite the age discrepancy. I figured he was the only person that fit the bill since he had a hood in his closet, and that the hood was like Hooded Justice’s costume. I thought, “It would be so clever if the KKK hood was a commentary on Hooded Justice’s true nature. Why else would he think of a noose and a hood as a viable costume choice?” I figured any age discrepancy could be explained by whatever clone nonsense Lady Trieu is cooking up. Funnily enough, Will Reeves did cross my mind. But as quickly as I thought it, I immediately dismissed it. “Nah, he can’t be. He’s Black,” I thought.

How wrong I was.

After seeing that Will was, in fact, Hooded Justice, it all made even more sense than I ever could imagined, and it commented beautifully and effortlessly on how America’s tendency to rewrite history could have made it possible for a Black man to be one of the heroes of New York without anyone ever knowing.

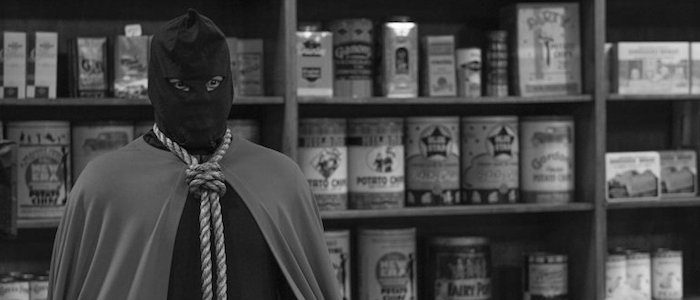

First, let’s take apart the costuming decision. Will’s decision to take on the pain that overt and indirect racism gave him on an hourly basis was a chef’s kiss of a decision. After being nearly lynched by the racist police, it only makes sense that, in his anger, he would take the noose that nearly killed him and use it to fuel his fury-filled punches.

Racism also gives us an understandable reason for why Hooded Justice was always the most ruthless of the Minutemen. He had bottled-up anger that followed him ever since he was a child. It’s the anger that needed to come out, frankly. Will’s anger is the embodiment of White supremacy’s karma coming back to bite it in the butt.

Hooded Justice is a tragic character, to be sure, and part of his tragedy is that in order to succeed, he had to whitewash himself. Throughout history, there have been so many Black accomplishments that have been whitewashed, some of which I cover in my book, The Book of Awesome Black Americans. One such accomplishment is the invention of the lightbulb. While Thomas Edison gets the credit, it was actually Lewis Latimer who actually developed the technology to make the lightbulb possible (and this was after he helped Alexander Graham Bell develop the telephone).

Another whitewash is ancient Egypt. You know how some folks believe that aliens had to have built the pyramids simply because the pyramids aren’t in a European nation? That belief is a form of whitewashing. The ancient Egyptians weren’t “White” by the standards that defined how the mainstream viewed Egypt for decades. There’s a complicated debate revolving around the genetic makeup of ancient Egyptians, but the fact that there even is such a debate shows how fiercely people, including academics, want to keep the modern view of ancient Egypt as a modern whitewashed myth instead of recognizing the multicultural and multiracial heritage of ancient Egypt.

Beyond the ancient Egyptians, Western history blocks out mention of the vast African kingdoms that existed before slavery and colonization. Such nations, which are also mentioned in my book, boasted extreme wealth, scientific and social advancements, and more. But you wouldn’t know it if you went by a standard school-issue world history textbook. Even some of the great thinkers of the day that we think of as White might have been African, including Aesop, who is now being theorized as being of North African background, with this name referencing the Greek name for Ethiopia, Aethiops.

All of this should illustrate the point of how intolerant the 1940s would have been to someone like Will. If we as a nation are just now unlearning some of the whitewashing I mentioned, think about how much people would be ready to discredit Will’s superheroism back then. They wouldn’t be ready to accept that a Black man could be a masked hero. If anything, they’d be ready to throw Will in jail for mercilessly beating up White people, even if those people were the bad guys. He would have been jailed simply for being Black, and he would have been called a criminal who infiltrated the Minutemen. In that sense, he had to make himself appear White.

But the layers of that decision trickle down the generations. This is something Will was already beginning to see within himself—he began to hate putting on the makeup, which reflected his growing battle with internalizing the racist ideas the outside world had about Blackness and Whiteness. But the mental dangers he was battling were crystalized when he saw that same internalized racism threaten his son, who put on the makeup trying to be like Will. Will didn’t want his son to see Whiteness as something more desirable than Blackness, and he quickly realized that he had been unwittingly teaching his son the opposite lesson.

Fastforward to Angela, who wears makeup in a similar fashion, but instead of using makeup for a White complexion, she uses jet black airbrushed paint. The two using makeup in a similar way cleverly references the theory of generational trauma and how certain learned experiences can show up in people far removed from the originating incident. But it also shows how Angela is more secure in her Blackness than even Will was. Whereas Will was forced to paint over his race in order to have the ability to become a superpower, Angela is able to embrace hers as her superpower.

A gut-check for White moderates

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is often quoted and misquoted by those who want to taint his words and meanings to fit their questionable whims. His words have been used to speak over racism, absolve White denial, and blame the Black American for their own inequality. But if you have any knowledge of Dr. King, you’ll know that the mainstream, sanitized view of the man is entirely incorrect. For example, he did preach nonviolence, but nonviolence wasn’t meant to be interpreted as inaction, a distinction that is missed by people using King’s words as a wedge between Black righteous anger and White awareness. This is how prejudiced football fans used King, for example, inadvertently believing that Colin Kaepernick’s action to kneel was a form of violence, and that “proper” action required Kaepernick to do nothing to upset their delicate constitutions for racial discussions. Nonviolent protesting, instead, is supposed to mean organized, militant protests that, through the act of non-retaliation, reflects and magnifies the unfair treatment on a wider scale, thus prompting social change.

This misquoting phenomenon is part of what King said is the biggest impediment to racial justice—the White moderate. To quote him, as he wrote in Letter From Birmingham Jail:

“First, I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Council-er or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action;’ who paternalistically feels he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a ‘more convenient season.’”

The White moderate is, indeed, one of the enemies in this episode, and the best example of that is Captain Metropolis, AKA Nelson Gardner. He is possibly the most insidious form of White moderate, in which he’s someone who believes himself to be not racist because of some other inequality he faces. In Gardner’s case, it’s the fact that he’s gay in a time when being gay meant being thought of as a degenerate. Yes, Gardner did face his fair share of strife, having to hide himself in the face of the mainstream public. But what a guise Whiteness is for him! With his blonde hair and blue eyes, he’s able to achieve the American dream in terms of optics alone. He’s seen as a capable leader, the idealized White American. But what guise can Will use for his Blackness or even his own sexuality? Gardner is still able to lord over Will in both professional and personal capacities because of the power the times’ racial politics allowed.

Another facet of the insidiously moderate is that they refuse to use their racial leverage to help the underserved classes. Instead, they do enough to seem like they are helpful on the surface. At the root, however, they are still scared of upsetting a racial status quo that benefits them. Case in point: When Will asks Gardner for backup after staking out Cyclops’ hideout. Instead of keeping his promise of giving Will whatever help he would need, he reneges. Not only does he say that Black people naturally fight themselves, he also said the Minutemen “don’t handle” issues involving Black people.

Gardner, like some insidious moderates, aren’t interested in truly getting rid of the underlying issues that keep racism afloat. Instead, they like mining the aesthetics of Blackness—our bodies, style, talents—for their own fetishized ideas. Note how Gardner seems to mostly use his relationship with Will for sex. Think about why Gardner might think Will is beautiful. While Will is a good-looking man, I don’t think Gardner was doling out sweet nothings because he thought Will’s soul was beautiful. I think he was only entranced by him because he was a Black body. The fact that Gardner suggested that he and Will have sex with their costumes on gives an inside look at what truly interests Gardner. For Gardner, his mask means White liberation and power. Will’s hood and noose were placed on him because he was a Black, powerless man. Whether it’s in the eyes of the Klan or Gardner, Will is just another Black body to be objectified and taken apart.

I hope that White audiences take the scathing critique this episode provided and take it to heart. There are many lessons to be learned here. One of the most important is to recognize the history of America and one’s place in it, racially and otherwise. People in power need to recognize what role they play and how they can use their power to help tip the scales more towards equality. At the very least, I hope this episode shows how the White moderate shouldn’t add to the stress Black people already feel.

While the critique is levied at White viewers, the critique can also go to some non-Black viewers as well, particularly those who have digested the stereotypes about Blackness that the Western world has created. One thing I want all people to do, particularly those of us in the same underserved boat, is to understand each group’s struggles. Those of us who are disadvantaged on the racial hierarchy all suffer by the same supremacist hand, so it would behoove us to abolish the number of stereotypes we hold about each other. Hopefully, this episode could be a starting point for some people.

There’s so much more I could say about this episode. There were so many Easter eggs that I caught, such as the Cyclops symbol being a Watchmen-verse “OK” symbol, now known as a symbol used by Neo-Nazis. There were also so many that I didn’t catch until they were pointed out to me, like the “Fred” guy possibly being one Fred Trump, Donald Trump’s grandfather. A teacher could literally develop an entire course around this one episode.

Y’all did good, Lindelof and co. This episode is one that will go undefeated for a very long time.

The post ‘Watchmen’ Uses Superheroes to Remind Us That American History Erases Black Accomplishments appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/2Ywnelm