21st Century Spielberg Podcast: ‘Bridge of Spies’ and ‘The Post’ Personify the Spielbergian Hero’s Quest to Do the Right Thing

(Welcome to 21st Century Spielberg, an ongoing column and podcast that examines the challenging, sometimes misunderstood 21st-century filmography of one of our greatest living filmmakers, Steven Spielberg. In this edition: Bridge of Spies and The Post.)

The Spielbergian hero is someone who not only does the right thing, but goes above and beyond. Someone who risks it all – life, limb, and reputation – for the greater good. And not some wispy, intangible greater good, either – oh, no. It’s not the belief in a better world; it’s the belief that the world we already have is as good as it’s going to get, if only we allow it. Spielbergian America is a place where the power is in the hands of the people, and all the people need do to make the country live up to its lofty goals is to fight for what’s right, no matter how daunting the fight may be. Two of Steven Spielberg‘s 21st-century films personify this perfectly, and, coincidentally enough, both star Tom Hanks: Bridge of Spies and The Post.

Part 6: Do the Right Thing – Bridge of Spies and The Post

Everyone Deserves a Defense

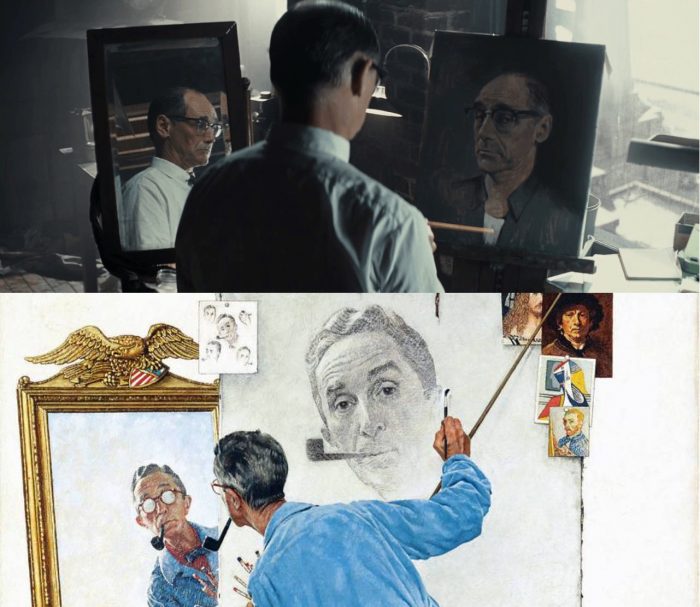

The first thing Bridge of Spies does is drop us into the middle of some Cold War spycraft. But this isn’t your typical movie espionage. There are no shoot-outs; no tuxedoes; no martinis, neither shaken nor stirred. Instead, the spy work being done in the opening moments of Bridge of Spies consists of a slight, quiet man painting. He paints his portrait – the shot set up to recall Norman Rockwell’s painting “Triple Self-Portrait” with three distinct things to look at – the man doing the painting, the mirror he’s looking into, and the canvas he’s recreated his visage on. And he also heads off to the park to paint some landscapes.

He’s an unassuming, unthreatening man, played by Mark Rylance, an actor who had primarily stuck to stage work and some minor film roles until Steven Spielberg came along. The character’s name is Rudolf Abel – but we don’t know that yet. We don’t really know anything yet, because Spielberg stages this opening in near-silence. Sure, there are the sounds of the Brooklyn neighborhood Abel lives in. And there are the sounds of the footfalls of the men in suits who seem to be tailing Abel around. But there’s no music; no drama, really. We’re dropped into this world and forced to go along with it until we can figure out just what the heck is going on.

Abel is a spy. He may not look like a spy – his clothes are shabby, the hotel room he’s staying in is a tiny mess, and his eyes are owl-like behind a pair of thick glasses. But right under the noses of all around him, Abel has been engaged in spycraft for the Russians. But now his time has run out – the FBI comes storming into Abel’s hotel room and hauls him away (although not before Abel is able to slyly destroy a secret document he had hidden in plain sight).

Now in custody, the accused Soviet spy needs a lawyer – and he gets one in James B. Donovan (Tom Hanks), an insurance lawyer at a prestigious firm. The American government’s position is that Abel deserves a defense – but not too good a defense. Everyone commends Donovan for taking the job, but they’re also not very subtle in their wishes for him to lose the case. Sure, Abel deserves the appearance of a defense – but as far as everyone around Donovan is concerned, the man is a commie spy who deserves to be strapped into the electric chair. Donovan’s bosses; his wife Mary (an unfortunately underused Amy Ryan); the U.S. Government; even the judge in the case – they all make it pretty clear that there’s only so far Donovan should go to do his duty.

But Donovan doesn’t agree. “Everyone deserves a defense,” he says. “Every person matters.” It’s a mantra he’ll repeat more than once. He’s that prototypical Spielbergian hero, and in the hands of Tom Hanks, he becomes a figure of unimpeachable integrity. Hanks is an actor who radiates nice guy vibes, so his casting here is pitch-perfect. As Spielberg put it:

“James Donovan was what you would call a stand-up kind of guy, someone who stands up for what he believes in, which, in his case, is justice for all, regardless of what side of the Iron Curtain you are on. He was only interested in the letter of the law. And Tom’s own morality and his own sense of equality and fairness, and the fact that he does such good things in the world by wisely using his celebrity, made him the perfect fit.”

Best of all, Hanks doesn’t make Donovan a total square. Sure, he’s a lawyer who is standing up for what’s right based on his almost fervent belief in the rule of law. But he’s also a funny guy, with Hanks’ natural comedic timing shining through. He and Abel click almost immediately.

“Have you represented many accused spies?” Abel asks during their first meeting, to which Donovan replies: “No. Not yet. This will be a first for the both of us.” It’s an ice-breaker moment that endears the men to each other. Donovan knows that Abel is a spy, but in his eyes, Abel is just a guy doing his job for his country – the same way that Donovan is. And he’s ready to fight like hell to defend the man. “I don’t work for the government,” he tells Abel. “I work for you.”

Donovan’s almost stubborn refusal to take the easy way out seems almost unbelievable these days. Can you think of a public figure here in the 21st century that would be so unflinchingly principled to do what’s right? I’m sure if you can the list is very, very small. But it also never seems phony in Bridge of Spies. We want to believe in upright men like James B. Donovan. We want to buy into Steven Spielberg’s firm belief in America.

America is not an abstract idea to Spielberg. And while the filmmaker didn’t write the screenplay to Bridge of Spies, you can feel his own personal belief system radiating off the screen. It’s perfectly encapsulated in a scene in which Donovan has a conversation with a CIA agent. The agent would very much like Donovan to ignore attorney-client privilege and spill whatever secrets Abel may have revealed (little does he know that Abel hasn’t given away anything – and never will. He remains tight-lipped about his spying activities, even when given the opportunity to give them up in exchange for freedom).

“Don’t go Boy Scout on me,” the CIA agent tells Donovan while pressing for answers. “We don’t have a rule book here.”

But Donovan doesn’t agree. “What makes us both Americans?” he asks the agent. “Just one thing. One. Only one. The rule book. We call it the Constitution, and we agree to the rules, and that’s what makes us Americans. That’s all that makes us Americans. So don’t tell me there’s no rule book, and don’t nod at me like that you son of a bitch.”

It’s a perfect speech, delivered perfectly by Hanks, who remains calm through the delivery, even when dropping that “son of a bitch” at the end. It’s not corny; it’s not overdramatic. It’s what Donovan – and, by extension, Spielberg – believes. We are not American by blood. It doesn’t matter where we came from; what country our family immigrated from to get here. What makes us American is our unspoken agreement to follow that rule book, the Constitution. That’s all that matters. It has nothing to do with nationalism. It’s all about just playing fair.

Despite a rather solid case – the FBI had no warrant to collect the items they did from Abel’s hotel room – Donovan loses and Abel is convicted. Everyone breathes a sigh of relief – Donovan can say he did his best, and everyone can move on. But the lawyer is far from done. First, he manages to convince the judge to give Abel a life sentence rather than send him to his death, reasoning that one day, the Russians might capture an American spy – in which case Abel could be used as a bargaining chip to get this metaphorical American spy back. Then, Donovan goes all the way to the Supreme Court to argue for an appeal.

Usually big Supreme Court scenes are saved for the end of a movie, but with Bridge of Spies, things are just warming up. As a result, this is almost two movies in one, with the first half dedicated to Donovan’s defense of Abel in America, and the second half taking the lawyer far from home. Donovan fails to sway the Supreme Court, and finally seems ready to accept that his work is done. In truth, his job is just getting started.

You Know What You Did

Jump to 1960, and Gary Powers, a pilot in the CIA’s top-secret U-2 spy plane program, has just gone and gotten himself shot down in the USSR. This is a big problem because getting captured is the one thing Powers was instructed not to do. As far as the CIA is concerned, Powers doesn’t exist. His mission, should he choose to accept it, is to commit suicide rather than fall into the hands of the Reds. But Powers is indeed captured, and paraded in front of cameras in a show trial meant to embarrass the United States. Which it does. Powers is convicted and locked up in Russian prison, but the Americans realize they have an ace up their sleeve to get him back – Rudolf Abel.

After a series of back-channel messages, Donavan is drafted by the CIA to head to Berlin to negotiate the swap. But Berlin is a powder keg at the moment. The Berlin Wall is going up, and Donovan will soon find himself in the middle of dealing with both the Russians and the East Germans. Before Donovan’s arrival, American student Frederic Pryor ends up arrested in East Germany and sent to jail on suspicion of spying. Donovan learns about Pryor’s capture when he arrives in Germany, but as far as the CIA is concerned, Pryor doesn’t matter. Powers is the objective.

But Donovan can’t let that go. He’s that Spielbergian hero, committed to not just doing his duty, but going above and beyond. He plans to arrange the release of both Powers and Pryor, but that’s easier said than done. The Russians and the East Germans keep bouncing him back and forth, resulting in confusion and miscommunication, almost all of it played for surreal laughs.

Bridge of Spies isn’t just a Steven Spielberg movie. It’s also a Coen Brothers movie. Sort of. Matt Charman wrote the initial draft of the script, and when Spielberg came aboard, he brought in Joel and Ethan Coen to polish things up. The Berlin section of the film is where the Coen’s style shines through, as nearly every character Donovan encounters seems plucked from a Coen-like farce (think a slightly-less-silly Burn After Reading).

“Joel and Ethan got us very, very deep into the characters,” Spielberg said. “They really instilled a sense of irony and a little bit of absurd humor, not absurd in the sense that movies can take license and be absurd, but that real life is absurd. They are great observers of real life, as we all know from their great august body of work, and were able to bring that to the story.”

While the first half of the movie is strong, the second half is when things really begin to sing, as Donovan treks around a snowy Berlin and comes down with a cold in the process. Donovan’s consistent sniffling and coughing adds an extra layer of amusement to the proceedings and helps to lighten what could’ve been a non-stop series of tension-filled scenes. Donovan is playing with fire here, putting his life, and the lives of Pryor and Powers in danger – and yet Bridge of Spies manages to find the humor in it all, be it in how Donovan keeps trying to sweet-talk his way to victory, or in how blatant the Russians and East Germans are in their lies and obfuscation.

Eventually, Donovan achieves the impossible. He’s able to convince both sides to give up their prisoners in exchange for Abel, with everything culminating in a thrilling, tense conclusion set both at Glienicke Bridge, where Powers is to be swapped with Abel and at Checkpoint Charlie, where Pryor is to be set free. So much of Bridge of Spies consists of people simply having conversations, but Spielberg is able to turn those conversations into cinematic thrills. Spielberg’s camera tracks Hanks’ Donovan anxiously waiting on the bridge while cutting over to Checkpoint Charlie, where a bored CIA agent waits for Pryor to show up. So much is riding on whether or not this will all go according to plan, and the tension builds.

It’s alleviated for a moment when Abel is brought to the bridge and he and Donovan reunite with a handshake that seems so warm against the winter cold. These men respect each other, and Donovan wants to make sure Abel survives all of this. In a sense, he cares more about Abel than does the American prisoners he’s arranged to have released.

Eventually, it works out. Abel returns to the Russians, Powers and Pryor are released, and Donovan heads home. On the flight back, the CIA are cold and standoffish to Powers. He wasn’t supposed to be captured, after all. But Powers insists to Donovan that he kept his mouth shut and gave away nothing to the Russians. But Donovan replies: “It doesn’t matter what others think. You know what you did.”

Because not only is the Spielbergian hero committed to doing the right thing, he’s also selfless. Even after all is said and done, Donovan returns home and doesn’t bother to tell his wife what he did – she has to find out via the TV news while Donovan is passed out upstairs. He’s done his duty without bothering to brag, and he can feel pretty good about himself.

Or can he? After a seemingly upbeat moment of triumph, all of it scored by Thomas Newman‘s gorgeous music (regular Spielberg collaborator John Williams was dealing with medical issues at the time, and Newman stepped in), Spielberg throws in one moment of dark doubt. In Berlin, Donovan watched in horror from a passing train as kids tried to scramble over the Berlin Wall, only to be shot in the back. Now, riding the train in America, he looks out and sees a group of kids leaping over a backyard fence. It’s framed exactly the same way as the Berlin Wall moment, and we almost expect gunfire to rain down on these fence-jumpers. But of course, that doesn’t happen. They go about their merry way – but Donovan looks on. He looks on for a long time, long after the train has left those kids and that fence behind. He did the right thing, and he knows what he did. But he’ll never be able to get certain images from the experience out of his head.

Kinship

Bridge of Spies is Spielberg at the peak of his power. It speaks to the filmmaker’s talent that he was able to turn Bridge of Spies – a talky, adult-driven drama that has nothing to do with franchises – into a box office success. That’s not always a given with a Spielberg movie, but Bridge of Spies managed to pull it off because of its inherent quality.

The filmmaker is clearly having fun here. There’s something thrilling about watching Spielberg set up moments like when Donovan tries to evade a CIA tail in the rain; or the back and forth dialogue between Donovan and nearly every character. Even the film’s one big action moment – Powers’ plane crash – radiates with innovation, like when Spielberg has the camera point up through a hole in Powers’ parachute to show the pilot’s spyplane disintegrating above.

“I can’t live on an alien planet my entire career,” Spielberg said in regards to the grounded, real-world story of Bridge of Spies. “I’ve got to find things that are earthbound that make me glad to be on this planet, and experiences, when I’m making films, that have relevance and have kinship to actual events in history. That fills me up; that makes me actually happier in this stage of my life than even a success like Jurassic World.”

Hanks’ stellar performance is a key ingredient to making this all work, and it’s hard to imagine any other actor in the role. But it’s also important to single-out Mark Rylance’s award-winning turn as the calm, polite Abel. The antithesis of the generic enemy spy, Abel is simply a guy doing his job, and Rylance brings such an air of poise to the part that it’s immediately endearing. Like Donovan, we can’t help but like this guy.

“What Mark brings to the role is a completely-realized self-assuredness. Mark will not take a moment and throw it completely out and come in and completely redo it,” said Hanks of his co-star. “What Mark will do instead is construct the character in the scene that slow little motions of feint, either one way or the next, will bring a new jolt of energy to, but is still the same character he built.”

Tying all of this together is a world that feels lived-in. The late 1950s-early, 1960s atmosphere never feels staged. The costumes the characters wear feel lived in. There’s a Rockwell-like nostalgia, sure – but nothing here feels idealized. Frequent Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kaminski plays around with a lighting style that will carry over into the similarly-themed The Post, where the interiors of rooms are dark and full of wafting smoke while bright, almost unearthly light blasts through windows. As bright as that light is, it also looks cold, which sells the wintry atmosphere most of the film is set in.

There’s a practical reason for the way the light burns through those windows: the glass has all been frosted over. Bridge of Spies was another quick shoot for Spielberg, and as a result of the fast-paced production, there wasn’t enough time to deal with greenscreens and digital historic settings. The solution: frost the glass so we can never really see what’s going on through certain windows. Like all great magic tricks, it seems kind of cheap when you realize how it’s done. But in the context of the movie, it works exceedingly well.

Kaminski also plays around with the lighting in the film’s locations – the United States, East Germany, and West Berlin are all lit in different ways. “When you think about the New York part, which is more golden, our perception of the period tends to be a little bit warmer, because it is in the past, so we tend to romanticize those images,” Kaminski said. “And also, the United States during that time was slightly more innocent, so the light and the color reflect that innocence to some degree. And then actually progressing through the film and going to West Berlin, [this] is still colorful, but not as colorful as New York. And subsequently, when you move to East Germany, there is a total void of color. It becomes not black and white, but desaturated and more bluish. And you achieve that by exposing the film a certain way, not putting color gels on the lights, but lighting with bluish and white light.”

But best of all, Bridge of Spies succeeds because of how deftly it sells its message without ever seeming like a “message movie.” This is a film with deep faith in America, but it’s not your typical flag-waving patriotic clap-trap. Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies isn’t interested in those abstractions, or that pageantry. It’s instead interested in shining a light on a rare individual willing to go the distance to uphold that rule book he believes so dearly in. This is a much-needed civics lesson wrapped up in a bright, shiny Spielbergian package. A rejection of blind, stupid, thoughtless nationalism for the sake of nationalism, and instead rooted firmly in the belief that the country is only as good as its people are willing to be. As a nation, we can all be better – if only more people were willing to believe in that rule book as much as James B. Donovan.

“I Might Be Crazy, But I Think I’m Going to Make Another Movie Right Now”

Steven Spielberg makes movies for everyone, but he primarily makes movies about men (and boys). There are plenty of Spielberg female supporting characters, some of them quite great, but the overwhelming body of Spielberg’s work consists of male-driven stories. And then, in his early ’70s, Spielberg went ahead and made the most feminist movie of his entire career: The Post.

There are plenty of male figures swirling about the character-driven saga, most notably Tom Hanks’ gruff newspaperman Ben Bradlee. But The Post is really a story about a woman, and how that woman – after years of being told to keep quiet and remain in her place – finally decided to speak up and wield the power she possessed.

That woman is Katharine Graham, played by Meryl Streep. Graham was never supposed to be an influential figure. Her husband, Phil, had inherited the Washington Post. And then, like his father before him, Phil Graham died by suicide. Phil’s death resulted in Katharine becoming the paper’s owner, which made her the first female publisher of a major American newspaper in the 20th century.

While the script for The Post would eventually be expanded to include many characters, it started out as the Kay Graham story. Liz Hannah had read Graham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning autobiography Personal History and come away inspired. “I had never read a memoir where somebody was so willing to talk about their mistakes and talk about their relationships and really analyze them,” the screenwriter said.

Hannah sent her script out to agents, never dreaming it would end up being a big movie with a big cast and a big director. In Hannah’s own words she thought the project would end up being “this tiny little movie that no one will ever see.” But of course, she was wrong. The script caught the eye of legendary producer Amy Pascal. Pascal would, in turn, send the script to Spielberg – who was doubtful, at least at first.

“I got a call from Stacey Snider and Amy Pascal, who suggested I read a script from a brand-new writer who’d never sold anything in her life — Liz Hannah, 31 years old — who had written a story about Katharine Graham,” Spielberg said. “I was reluctant to read the script, but Stacey and Amy said, ‘I think you’ll change your mind…’ And I did.”

The aftermath of the election of 2016 ignited in Spielberg a passionate fire to get The Post made. “The level of urgency to make the movie was because of the current climate of this administration, bombarding the press and labeling the truth as fake if it suited them,” Spielberg said after the film was made. “I deeply resented the hashtag ‘alternative facts,’ because I’m a believer in only one truth, which is the objective truth.”

The urgency resulted in a prototypical Spielbergian case of overachievement, with the filmmaker stepping away from post-production on his impending Ready Player One to shoot The Post. “Liz’s writing, her premise, her critical study and especially her beautiful, personal portrait of Graham got me to say: ‘I might be crazy, but I think I’m going to make another movie right now,'” Spielberg later recounted. “It snuck up on me.”

The Post producer Kristie Macosko Krieger added: “We just turned everything around in a day. I called everybody and said…’we’re going to make a movie in New York in 11 weeks.'” After those weeks of pre-production (it ended up being 12, not 11), Spielberg completed shooting on The Post in two months (the entire process, from pre-production to release took only seven months). He had flexed his powers to put together a huge cast – mostly comprised of actors acclaimed for their TV work – and put at the head of that cast Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks.

Spotlight screenwriter Josh Singer also came aboard to expand Hannah’s script. “Liz’s script was about two human beings on an intimate journey, an incredible script,” Singer said. “What we then wanted to do was add in more history and a strong sense of the timeline to show how remarkable these few days were and bring the audience deeper into that world. We move beyond Kay and Ben to see what’s going on with the Nixon tapes and with The New York Times and it all helps create more context for Kay’s massive moment of decision-making.” The end result may not be Steven Spielberg’s best movie – but it is one of the most entertaining, and rewarding. It’s a breezy, fast-paced, star-studded masterclass on doing the right thing, and lobbying praise on the sanctity of the press.

Let’s Go

The Post tells the true story of the publishing of the “Pentagon Papers,” a set of classified documents regarding the 20-year involvement of the United States government in the Vietnam War, loaded with plenty of proof that America knew that there was no way to win the war, but was too proud to admit it or pull out of the conflict. The papers were leaked to the press by military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, played in the film by Matthew Rhys.

Vietnam is mostly in the background of The Post, but Spielberg can’t resist dropping us into the war by showing Ellsberg in the midst of the conflict, complete with a groan-inducingly predictable Creedence Clearwater Revival cut blaring over the soundtrack. At some point, someone decided Creedence was the official music of the Vietnam War, and Spielberg was unfortunately not above falling into the trap.

Ellsberg knows the war is going poorly, and he says as much to then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. But later, Ellsberg watches in horror as McNamara lies to the press about the war with a smile on his face. The story then jumps forward a few years – without really clarifying that, making it look as if this is all happening in the span of a few days. Now working as a civilian-military contractor/consultant for the RAND Corporation, a military thinktank, the still disillusioned Ellsberg decides to do something: he photocopies hundreds of pages of classified documents pertaining to the war. Documents that stretch back to the Truman administration. Documents that make it abundantly clear that the United States has known Vietnam was a lost cause for years, and yet continued to send troops off to their death rather than admit defeat.

Spielberg stages these opening moments with all the urgency of a paranoia-tinged spy thriller, with Ellsberg on edge as he hustles about, photocopying documents. To better illustrate how far back the words in these documents go, and to make the scene all the more exciting, Spielberg juxtaposes footage of various presidents giving speeches about the conflict against scenes of Ellsberg photocopying pages while reading off dates and excerpts. Over it all, John Williams’ score is like a ticking clock. It even recalls the music he created for the “stealing of the embryos” scene in Jurassic Park, and while The Post is far removed from that fantastical film, this theft scene has almost the same energy. In short, it’s thrilling. In the span of a few minutes, Steven Spielberg manages to make a man photocopying some pages look just as exciting as a car chase sequence.

After the Ellsberg intro, The Post moves on to our main characters. We meet Katherine Graham (Meryl Streep), the owner of The Washington Post. She’s always the lone woman in a room full of men – a motif Spielberg returns to again and again, with Graham always sticking out among a sea of business suits. It’s 1971, and the Post is still considered a “small local paper.” That might soon change, though, as Graham plans to take the paper public, hoping the stock market launch will improve financial matters.

Graham clashes with the Post‘s editor, the gruffer-than-gruff Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks. The first scene that the two share starts off playful, even friendly. But it becomes clear that Bradlee has a bad habit of talking over Graham. And at one point, when she makes a suggestion about publishing something, Bradlee snaps at her. It renders Graham momentarily silent, and the character’s silence is something Streep does wonderful work with.

I know it’s almost cliched at this point to point out what a great actress Streep is, but she does some of the finest work of her career in The Post. The part allows Streep to constantly be just a tiny bit off-kilter – Katherine doubts herself. During a meeting with the Post‘s board, when given the opportunity to talk using a series of notes she spent all night working on, Katherine clams up, preferring instead to let Chairman of the Board Fritz Beebe (the always-welcome Tracy Letts) speak for her. During the same meeting, when someone asks for a monetary figure, Graham has the answer, but she only whispers it to herself. No one hears her.

The relationship between Bradlee and Graham is ultimately warm and caring, but it takes almost the whole film for Bradlee to really realize how much of a risk Graham is taking. But as the narrative kicks off, Bradlee is more worried about the Post‘s reputation. He’s angry their stories aren’t big enough; aren’t groundbreaking enough. He’s worried no one takes them seriously. Hell, they can’t even get an invite to Richard Nixon’s daughter’s wedding at the White House.

But everything is about to change. The New York Times starts publishing the Pentagon Papers. Soon, the Post gets some of the papers themselves. And then one of their staff, assistant editor Ben Bagdikian (Bob Odenkirk, who is phenomenal here, giving a memorable but understated performance) realizes he knows where the papers are coming from. He has a connection to Ellsberg, and manages to track the man down and retrieve even more of the stolen documents.

However, things have gotten complicated. A federal district court injunction has stopped the Times from publishing more of the papers. Bradlee says that shouldn’t be a problem – the injunction was against the Times, not the Post. He wants to publish them. He needs to publish them. Not just for the sake of the Post, but also because it’s a First Amendment issue. The government has never before stepped in like this against a newspaper. “The only way to protect the right to publish is to publish,” Bradlee says. Hanks is having fun with this part. It’s not his most nuanced work, and his scratchy voice is a little distracting (as is his wig). But Hanks realizes that this isn’t his movie – it’s Streep’s. Bradlee is just a supporting player, and Hanks knows just how to dial things back so that he never takes over the picture. He also gets quiet moments to shine, such as when Bradlee reflects on how his close friendship with John F. Kennedy surely got in the way of how he covered the JFK administration.

While Bradlee and his staff are raring to publish, everyone who is not on the writing side of the Post – the lawyers, the board members, the money men – thinks it’s a terrible idea, and they make sure their objections are heard by Katherine. But Katherine is clearly conflicted. She knows that Ben is right – that publishing is important. But like James B. Donovan in Bridge of Spies, almost everyone around her is telling her it’s wrong. Even Fritz, who is always ready to defend Katherine, tells her he probably wouldn’t publish.

This all builds to one of Spielberg’s most enjoyable bits of filmmaking, coupled with tour de force work by Streep. Katherine is on the phone with Ben and the lawyers. Ben is yelling that they should publish. The lawyers are yelling that they shouldn’t. The camera starts off above and behind Katherine, slowly circling around to her face as she stands alone in a room in her house, clutching the phone. Katherine is being told that journalists will resign if they don’t publish. Ben adds that if they don’t publish: “We will lose. The country will lose. Nixon wins. Nixon wins this one, and the next one, and all the ones after that. Because we were scared. Because” – and here he repeats his mantra – “The only way to protect the right to publish is to publish.”

Spielberg starts pushing in on Katherine’s face. Streep widens her moist eyes; her breathing begins to increase; she cocks her head to the side and bites her lower lip. She looks ready to say something, anything. But the words aren’t coming – not just yet. Not till the camera gets to where it needs to be. First, it has to push in on Streep’s face as she struggles to find the right words. And then, when the camera hits its mark, and when Streep’s face is filling the frame, she blurts out: “Let’s go. Let’s do it.” And she slams the phone down before she can have her mind changed.

It’s dynamite. It’s electric. On paper, the scene is simple – Katherine hesitates, then gives her answer. But in Spielberg and Streep’shands, it’s a scene that gets your heart pumping in your chest.

Brave

The publication kicks off a firestorm from the Nixon White House. Spielberg makes the rather odd decision to make Nixon a sort of comical boogeyman – playing audio recordings of Nixon’s phone calls against shots of an actor playing Nixon pacing around the Oval Office. Spielberg never goes inside the Oval – we just hang out on the lawn, peeking in through the window.

Remember what I said about Bridge of Spies – how big Supreme Court scenes are saved for the end of a movie? It wasn’t true in that film, but it is here. Graham and Bradlee go to the Supreme Court to argue their First Amendment constitutional rights, and – spoiler alert – they win. The court decision is read out by editorial writer Meg Greenfield, played by a criminally underused Carrie Coon who none the less gets what might be the most important speech in the film: “In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors.”

It’s a big, triumphant moment. It’s Spielberg and company striking a blow for the First Amendment and reminding us that the Trump years weren’t the only time that Republican administrations attacked the press. And Spielberg, that eternal optimist, wants to remind us that this is a fight worth having. That the only way to protect the right to publish is to publish. “We’re telling the story of resiliency, honesty and dedication of the whole career of journalism,” Spielberg said. “Some would have us believe that there is no difference between beliefs and facts. We wanted to make a story where basically facts are the foundation of all truth and we wanted to tell the truth.”

For all of its wonderful, important, and timely moments, The Post trips over its own feet on more than one occasion. The Vietnam opening is unnecessary. The spooky shots of Nixon through the White House windows are distracting. And, worst of all, Spielberg tacks on an ending that feels like he’s trying to set up The Post Cinematic Universe. After all is said and done, Katherine and Bradlee share a warm moment together where they commend each other for doing the right thing. And then Katerine says, “I don’t think I could ever live through something like this again!” At which point – after a brief Nixon moment – Spielberg cuts to the Watergate break-in, complete with a guard saying, “I think we have a break-in at the Watergate Hotel!” It’s groan-worthy, as if Spielberg is winking at us as he sets up the events covered in All the President’s Men – a movie that doesn’t feature Katherine Graham, but does feature Ben Bradlee, played by Jason Robards.

But these missteps are minor compared to all the wonderful work Spielberg does here. It’s the little things that matter: the way Bradlee and two writers run down to the newsstand to grab the New York Times, and pages of the paper blow out of their hands and flutter overhead like birds. The way Spielberg cuts to a shot of everyone in the Post newsroom with their nose in the Times. The way the printing press in the Post‘s basement rattles the whole building when it’s turned on, as if it’s some ancient slumbering god shaking itself awake.

And then there are those performances. While some actors are underused, they all get at least one moment to shine. The best example of this might be Sarah Paulson, who is stuck in the thankless task of playing Bradlee’s wife Tony. Paulson spends the majority of the movie just hanging in the background, and just when you think she’s about to be completely underserved by the movie, she ends up with a wonderful speech where she finally makes Ben realize just how brave Katherine is being by agreeing to publish the papers:

“Kay is in a position she never thought she’d be in, a position I’m sure plenty of people don’t think she should have. When you’re told time and time again that you’re not good enough, that your opinion doesn’t matter as much. When they don’t just look past you, when, to them, you’re not even there, when that’s been your reality for so long, it’s hard not to let yourself think it’s true. So to make this decision, to risk her fortune and the company that’s been her entire life, well, I think that’s brave.”

Spielberg usually storyboards for his films, but the rushed production of The Post made that impossible. Instead, the filmmaker relied on his actors to help him create his shots. “Every single shot was discovered through the discovery of the actors’ performances,” he said. “When you get performances like this and a company of actors like that, the shots are coming at me fast — I’m having trouble keeping them in my head how I want to shoot the scene — but I came to work every day with an open mind without a shot list…The same way the actors never rehearsed, everything was done in the moment and very spontaneously.”

And then there’s the look of the film. The blown-out window light from Bridge of Spies is back, but there’s an old school feel to the footage due to cinematographer Janusz Kaminski shooting on 35mm film. “I wanted with Janusz to make the film look like it was not a contemporary film but rather shot in the early 1970s,” Spielberg said. “It was all about color temperature and palette and coordinating Janusz’s lighting with Ann Roth’s brilliant costumes.”

Clocking in at 116 minutes, The Post whizzes by. There’s not an ounce of fat on this thing – it flies off the screen and never overstays its welcome. And, most remarkable of all, it has a woman as the Spielbergian hero. Spielberg was 71 when he made The Post, and yet even at that age, he was showing that he still had plenty of tricks up his sleeve. That he could still pump out a thrilling, challenging film better than any filmmaker half his age working at the time, and that he could try new things. But Bridge of Spies and The Post were both grounded, character-driven films set in the real world. And Spielberg wasn’t done yet. He still had two other films arriving in the 21st century, both of which returned him to effects-driven fantasy, for better or worse. Mostly worse. But that’s a story for next time.

The post 21st Century Spielberg Podcast: ‘Bridge of Spies’ and ‘The Post’ Personify the Spielbergian Hero’s Quest to Do the Right Thing appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/37b9l27

No comments: