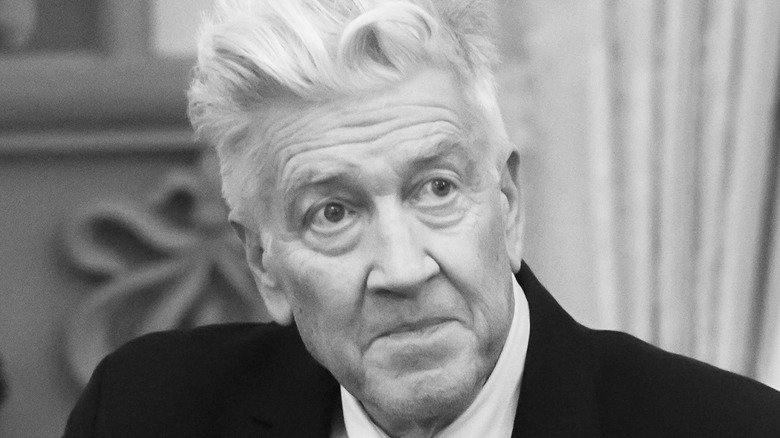

David Lynch's Feature Films Ranked From Worst To Best

David Lynch's movies are obsessed with the persistence and failure of identity, so it's not surprising that his 10 films are both like and unlike themselves. His movies circle around the same actors (Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, Harry Dean Stanton), the same genres (noir, melodrama), the same themes (disability, sexual violence, infidelity, meta-film), and the same distinctively surreal, or hyper-real, absurdist visuals. But over his career Lynch has also continually pushed the boundaries of his own style, shifting from narrative-free experiments, to genre movies, to big-budget blockbusters, to wholesome kids' movies, and ultimately moving away from film altogether for the smaller box of television.

Ranking Lynch's films is tricky both because they're so similar -- they almost seem to comprise a single work -- and because they're so different. How do you compare a space opera to a 19th-century biography, or either of those to a the three-hour jumble of genre tropes?

Be that as it may, we've been tasked with bringing a formal Lynchian order to the improvisatory Lynchian mess, and so we shall. Every one of Lynch's films at least looks lovely, and there's something of interest in even his worst efforts. But inevitably, some of his movies are better than others. Here, then, is the definitive list of all 10 David Lynch movies, ranked from "Don't you look at me!" to "Damn fine coffee."

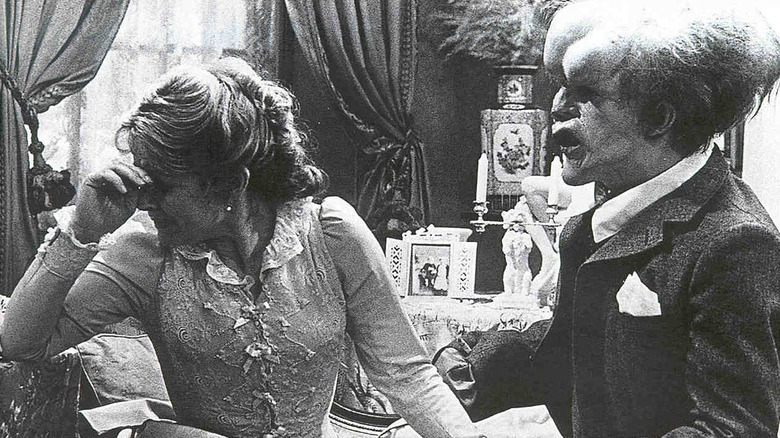

The Elephant Man

As a filmmaker, Lynch is most interested in exploring dream states and the places where genre tropes crumble into the subconscious. A somber biographical film seems completely ill-suited to his talents -- and, sure enough, his second movie, "The Elephant Man," is an aesthetic and ethical mess. The movie supposedly tells the story of John Merrick, a London man who suffered from extreme deformities, probably as a result of Proteus Syndrome.

In fact, though, Lynch is much less interested in Merrick's life than in the horror, pity, and sympathy he inspired. The movie refuses to show Merrick's perspective; instead, it keeps putting him on display for others. In an unforgivable choice, Lynch keeps Merrick (John Hurt) hidden from viewers for a long stretch at the beginning of the movie; when we finally see him, it's through the eyes of a maid who shrieks and runs screaming.

The film delights in heaping indignities on Merrick. It makes up a whole episode in which Merrick is captured and returned to a freak show as an excuse to include further scenes of Merrick being beaten and humiliated. His doctor, Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins), occasionally worries about whether he is exploiting Merrick, but this adds depth to Treves, not Merrick. The film itself doesn't make any honest effort to address the problem of representation.

For his part, Merrick is rarely allowed to express bitterness or anger or to demand equal treatment. The one exception is a mob scene that is lifted fairly obviously from "The Merchant of Venice." "I am not an animal!" Merrick shouts, and Lynch seems to think we should be impressed by this elementary observation. The plot veers between voyeuristic disgust and smug satisfaction at its own broad-mindedness. Lynch has yet to make another film as tedious and tone-deaf.

Lost Highway

"Lost Highway" has one of Lynch's cleverest narrative structures. The protagonist, saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) murders his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) and is convicted. Then, in his jail cell, he changes into a different person -- auto mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). The plot loops, as mysteries from Fred's life rhyme with the mysteries in Pete's. At times, Pete seems to be Fred's lost past; at others, Fred seems to be Pete's.

Unfortunately, this all sounds more fun than it is. The movie snags ideas from Lynch's earlier projects and reworks them in less insightful ways. It uses noir tropes without the flamboyant exuberance of "Blue Velvet"; it depicts a lover's heist without making you care about the lovers like you do in "Wild At Heart"; it features an abuser with multiple personalities, but without the sympathy for his victims that makes "Fire Walk With Me" so painful and terrifying. Swapping people's identities renders it difficult to make them distinctive or interesting, and Lynch refuses to commit to any clear theme beyond the misogynist film noir trope that women who have sexual autonomy are evil. Lynch attempts to hold your interest with a lot of topless scenes and some dramatic violence. Unfortunately, since most of us can't change into someone else halfway through its runtime, "Lost Highway" ends up being a slog.

Inland Empire

David Lynch's final film is a bold departure. It is entirely composed of scenes of Laura Dern starting to say something, and then changing her mind, interspersed with lights flickering. It is 150 hours long.Okay, okay, it's not quite that long, but it can feel like it. The real runtime of "Inland Empire" is "only" 180 minutes, and there is a vague plot of sorts. Dern plays Nikki Grace, an actor appearing in a (possibly) cursed experimental film about an adulterous love affair. Meanwhile, Nikki herself carries on an adulterous love affair with her co-star. Nikki maybe thinks she's becoming her character, and maybe is becoming her character. Also she's haunted by ominous Polish people and sex workers, the latter of whom occasionally perform girl-group dances to songs like "The Loco-Motion." To add to the confusion, Lynch includes scenes of a sitcom featuring an anthropomorphic rabbit-headed family and a loud laugh track.

There are fans who swear by "Inland Empire," and then there are fans who swear at it. The movie has some undeniably fun bits. Lynch shot it on hand-held digital video, and its grimy look is engagingly unusual. He uses clever cuts so you're not sure if you're watching the film or the film within the film. Dern's extended monologue about gouging a rapist's eye out is compelling, as is the visual image of her face twisted into a bizarre laughing mask. But, for me at least, the movie's studied, deliberate refusal to develop interesting characters, provide a plot, or to say anything gets old after three hours.

The Straight Story

A G-rated David Lynch picture released by Disney sounds like a dubious proposition, but "The Straight Story" works surprisingly well. Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth), 73, with poor eyesight and a bum hip, learns that his estranged brother has had a stroke. So, he buys a John Deere mower and travels from Iowa to Wisconsin to see him, having some heart-warming encounters along the way. If you're a sucker for sentimental Americana, this is of significantly higher quality than the genre usually manages. Lynch's panoramic views of the Midwest are lovely, the soundtrack is Angelo Badalamenti's most meltingly romantic, and Farnsworth, who was ill with cancer at the time, turns in a wonderfully low-key performance.

On the other hand, if sentiment makes you itch, at least "The Straight Story" contains some interesting insights for Lynch fans. After seeing it, for example, it's clear that the over-the-top portrayal of small-town life in "Blue Velvet" isn't meant entirely derisively. The way that "The Straight Story" treats aging suggests that Lynch has grown since making films like "Eraserhead" and "Elephant Man," in which disability is shown from the abled's perspective and treated like an object of horror and pity. You could argue that the "The Straight Story" is inspiration porn, but at least its story is told through Alvin's eyes. He gets to be the hero of his own narrative. The movie is slight, but it's hard not to applaud Lynch for trying something so different.

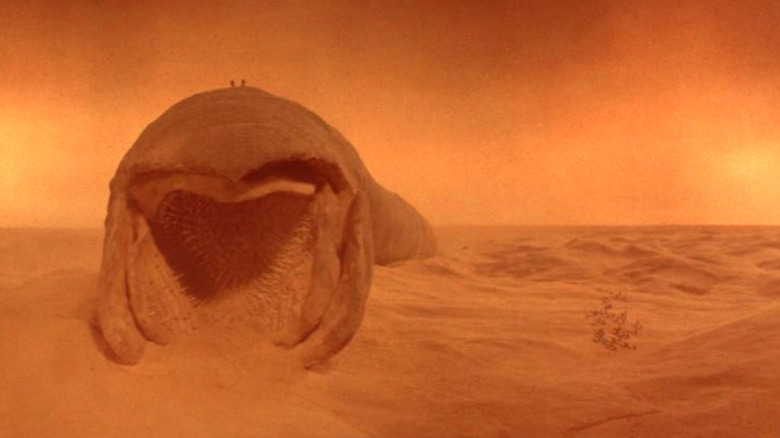

Dune

"What if Star Wars, but with every iota of fun surgically removed?" That is probably not the question that Universal Pictures was asking, but it is the call that David Lynch answered (or at least what Universal ended up with after denying Lynch the final cut of "Dune").

Dropped into the great desert of Hollywood blockbusters with only Frank Herbert's bloated and pompous science-fiction novel as a guide, Lynch created a world even more bloated, even more pompous, and even more drug-addled. The cast led by Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides (aka Maud'Dib, Usul, etc.) intones sententious quasi-New Age nonsense ("Fear is the mind killer," "They tried and died!") with an effect as flat as the gorgeously chintzy matte paintings. Great worms of exposition rise to the surface bellow hollowly, only to sink once more beneath the towering drifts of plot.

It would be a stretch to call "Dune" good, or even adequate, but it has an undeniable "Plan 9 From Outer Space" type of appeal, full of pulp tropes and blue contact lenses and odd stunt casting (Patrick Stewart? Sting?!). This is Lynch's one true venture into utter trash, and if you can get through it without giggling in delight a time or three, then you may be the Kwisatz Haderach himself. Or maybe you're just taking the wrong drugs. Who knows?

Eraserhead

David Lynch's stunning debut remains a weird touchstone for art cinema snobs and lovers of the surreal. The soundtrack alone is a work of genius, all echoing industrial hiss and haunting ambient clatter. Similarly, many of the black and white visuals -- Henry (Jack Nance) framed in a halo of his own hair, Henry cutting into a miniature chicken that thrusts its legs sexually and oozes blood -- have become icons of goofy oddball dread.

The loose narrative is also, contradictorily, one of Lynch's most thematically focused. Henry seeks love and finds instead gross bodies, sexual repulsion, and an ugly twisted child-thing that whines and mewls and demands care. It's a coming of age movie for the repressed sexual dysfunctional. Lynch's daughter Jennifer was born with two club feet, and the film reads like an autobiographical nightmare exploring Lynch's insecurities about fatherhood and his fascination with -- and loathing of -- disability and broken bodies. "Eraserhead" can drag a bit, and as a parent I find Lynch's metastasizing self-pity in the face of a child's suffering irritating. But, despite later homages like "Tetsuo: The Iron Man," there's nothing else in cinema quite like "Eraserhead."

Mulholland Drive

"Mulholland Drive" was originally supposed to be a television pilot, and it has an unfinished feeling. Several scenes (a hysterical botched hit, an unnamed character encountering a man from his dreams in a diner) seem like they were randomly pasted in from a larger work.

This isn't exactly a weakness. The movie is about Hollywood and the process of assembling movies from money, dreams, more or less fortunate actors, and happenstance. A young actress named Betty (Naomi Watts) meets an amnesiac named Rita (Laura Elena Harring), and the two try to piece together her story -- creating their own movie, as it were, until they fall in love. Then, as movie projects sometimes do, the whole thing unravels.

One common interpretation of the movie is that it's a hallucination of failed actress Diane (also Naomi Watts) -- a sort of "Sunset Boulevard" meets, well, David Lynch. However, you could also see "Mulholland Drive" as Lynch cheekily demonstrating that movies still hold your attention even when you know they're fake. To demonstrate the artificiality (and magic) of cinema, Lynch employs numerous tricks -- narrative fissures, two actors playing the same character, one actor playing two characters, and so on. His main weapon, though, is Naomi Watts, who plays an eager ingenue, a bitter, desperate murderer, a new love, and an old love, and handles scenes within scenes in an absolutely bravura fashion. Watts steals the show by showing that it's all a show, which makes it perhaps the Lynch-iest performance in his entire oeuvre.

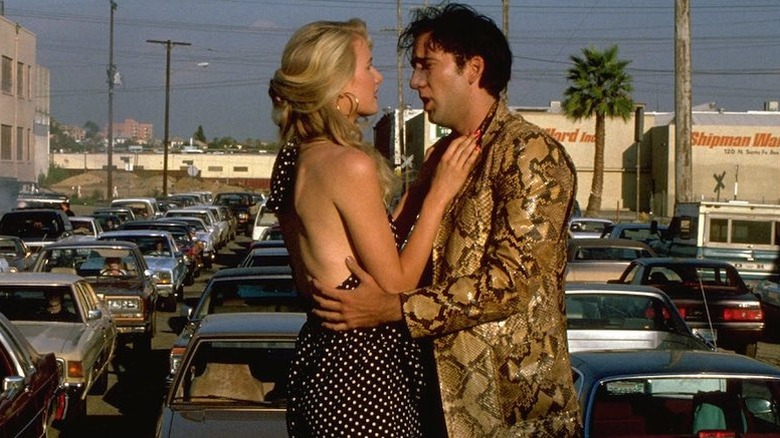

Wild At Heart

Roger Ebert wrote a scathing review of "Wild At Heart" when it was released. He despised the opening scene, in which Sailor (Nicolas Cage) murders a Black killer hired by his girlfriend's mother, Marietta Fortune (Diane Ladd). The film, Ebert argues, tries to excuse its violence and cruelty as "parody." It is, he says, "a film without the courage to declare its own darkest fantasies."

Lynch's attitude towards his material is always a little difficult to parse, and there are certainly elements of mockery in his depiction of lovers Sailor and Lula (Laura Dern). But to me, Lynch's belief in the characters is as sincere as anything in his work; he loves the couple, and wants you to love them, too. Yes, Sailor's Elvis accent and snakeskin jacket (his "personal symbol of individuality") are silly, and Lula's enthusiastic ode to his genitals is both saccharine and gross.

But love is silly, saccharine, gross, and wonderful all at once, and Cage and Dern make it unequivocally clear that they care for each other, whether they're stopping the car to dance to speed metal or having hard conversations about past betrayals and traumas. They overcome Lula's mother's (hyperbolic) opposition, their own (incredibly) poor choices, violence, and prison. And unless your heart is a big old lump of rock (or you're Roger Ebert, I suppose), you've got to swoon at least a little when Sailor serenades Lula with "Love Me Tender" on the hood of her convertible. Lynch, the stylized absurdist and cold-hearted weirdo, manages to succeed where rom-coms often fail: he gives you a unique couple who obviously care for each other, and who you can imagine being happy together.

Blue Velvet

Lynch's first noir is also, inevitably, his first meta-noir. "Blue Velvet" functions like a straightforward genre exercise, with the morally ambivalent hero Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan) torn between wholesome good girl Sandy (Laura Dern) and the dark BDSM charms of seedy nightclub singer Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini). But "Blue Velvet" is also a mash-up, inspired as much by Douglas Sirk as Jim Thompson, in which the manicured lawns of a wholesome suburbia peel back to reveal insects chewing on ears in the grass.

The most famous scene is ostentatiously about gaze. The viewer peers with Jeffrey through the slats in a closet as Frank (a manic Dennis Hopper) breathes through some sort of gas mask while spewing profanity, chewing up the scenery, and raping the masochistic Dorothy, who appears to be aroused despite herself. Jeffrey, like Jimmy Stewart in "Rear Window," wants to watch depraved sexual violence, but he also wants to watch the corny '50s sitcom version of this world, where high-schoolers talk about robins and love.

Jeffrey's aunt watches a robin feeding at the very end of the film and exclaims, "I don't see how they could do that. I could never eat a bug." But the horror (or the joke) of "Blue Velvet" is that Jeffrey, the viewer, and Lynch himself like eating bugs -- and like to recoil from robins eating bugs as well. Lynch would explore the combination of innocence and corruption again in "Twin Peaks," but "Blue Velvet" is where he perfected his view.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

The first half hour of this 135-minute film involves quirky FBI agents tussling with local law enforcement and using tailored dresses as secret code; it's as if Lynch wanted to lull fans of the TV series into a false sense of security. After that, the movie shifts to the last days in the life of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), and becomes an unrelenting portrait of sexual assault and incest.

In other contexts, Lynch's over-the-top melodrama and unexplained nightmare imagery can come across as humorous or self-indulgent. Here, though, every excess of Lynch's style is simply and chillingly apropos. Laura's father has a limitless, supernatural power to hurt her, whether he's demanding that she clean her fingernails at dinner or dragging her into the Black Lodge while possessed by the wood spirit Bob (Frank Silva). The line between reality and supernatural terror collapses not because Lynch is being showy, but because nothing imaginable can be worse than what happens to Laura, who Lee brilliantly portrays as clinging to her own humanity through a veil of drugs, hypersexuality, terror, and self-loathing.

When "Fire Walk With Me" was first released, the critical response was shockingly callous; Todd McCarthy at Variety actually called Laura -- a victim of protracted, repeated, violent sexual assault -- a "tiresome teenager." In recent years, though, the film has started to receive its due. Though "Fire Walk With Me" has been labeled incomprehensible, it's past time to see it for what it is: Lynch's most straightforward film, his saddest, and his best.

Read this next: Sight And Sound's Best Films Of 2017 List Inexplicably Includes 'Twin Peaks'

The post David Lynch's feature films ranked from worst to best appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/3jeeHPM

No comments: