The 15 Best Spy Movies Of All Time

In a 1956 letter to noir legend Raymond Chandler, Ian Fleming referred to his James Bond novels as "pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety." The phrase would eventually be turned around and immortalized as hepcat slang for spy cinema around the world. The business of kiss kiss, bang bang has been booming ever since. Fleming's creation for Queen and Country is now the second-longest running franchise in film history. "Mission: Impossible" has been playing in theaters longer than it ever aired on TV. Every few years, a new parody takes aim at the espionage du jour -- "Austin Powers," "OSS 117," "Kingsman" -- and invariably spawns its own ongoing franchise.

Spies and movies were made for one another. So long as there are international incidents, audiences will line up to watch fictional people prevent them. Factions rearrange their acronyms. Frictions boil over into bureaucratic friendships. But secrets, suspense, and sex never go out of style, and neither have these 15 films.

Spy Game Epitomizes The Thrillers Of Tony Scott's Later Career

At the end of a folksy story about a veterinarian who offered to put down his uncle's plow horse, retiring CIA agent Robert Redford comes to a cold point: "Why would I ask somebody else to kill a horse that belonged to me?"

Like every line in "Spy Game," it reads at least two different ways, neither definitive, both useless on the record. This is the native tongue of intelligence -- a willful lack thereof. All the suits gathered for Redford's last-day-on-the-job interrogation speak nothing else. In the field, like the Chinese prison where apprentice Brad Pitt rots, that language is about as useful as a party trick. That leaves Redford to negotiate his protégé's freedom while simultaneously denying it to his superiors, who'd just as soon disavow their prize thoroughbred.

It's dizzying by design. "Spy Game" is the first fully-formed example of director Tony Scott's late style. Scenes aren't shot so much as strafed -- the use of helicopters to film a personal rooftop conversation confused Redford until the premiere.

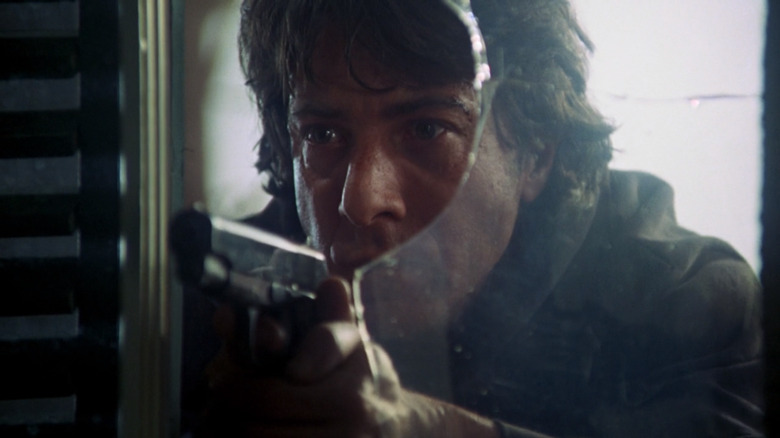

Marathon Man Debuted The Steadicam — And One Of Cinema's All-Time Great Villains

"Marathon Man" begins with hypnosis, but not the kind that shows up later on this list. This kind only affects the audience. In October 1976, they'd never seen anything like it. "Bound for Glory" was the first film to use the Steadicam system, but "Marathon Man" beat it to theaters by two months. Dustin Hoffman debuted it at jogging speed. The serenity is uncanny. Before a word is said, everything is wrong.

But Hoffman's Babe doesn't know any better. He can sleep easy knowing his big brother, Doc (Roy Scheider), is a run-of-the-mill businessman. In just a few short days, though, he'll become intimately acquainted with the investment potential of Nazi war crimes and the dangers of incompetent dentistry. Like the novel from screenwriting great William Goldman, "Marathon Man" tangles and unravels but marches on with the grim inevitability of rising water in a locked room. By the end, viewers gasp on Hoffman's behalf. By the time Sir Laurence Olivier asks his infamous question -- "Is it safe?" -- the audience breaks for him.

Murderers' Row Is A Spy Spoof Starring A Pitch-Perfect Dean Martin

Before Austin Powers and even our man Flint, there was Matt Helm. The character originated in a series of novels with 27 installments by author Donald Hamilton. Beyond the titles, none of those matter. As much as any role ever has been, the cinematic Helm is defined by its originator. Matt Helm was Dean Martin.

In this, his second of four on-screen misadventures, Matt Helm receives orders from a tape recorder hidden in a bottle of Irish whiskey he instinctively opens while driving. That's as potent a mission statement as any for the Matt Helm saga. He's charged with stopping maniac-of-the-week Karl Malden, who wants to aim a magnifying glass at Washington. It's just an excuse for Dino to charm his way across the French Riviera -- studio sets built to match -- drop innuendo around his latest costar -- Ann-Margret, incandescent -- and fiddle with a comically impractical gadget -- a delayed-trigger pistol that assumes all evildoers will stare down the barrel to check if it's loaded.

In Helm's world, they always do.

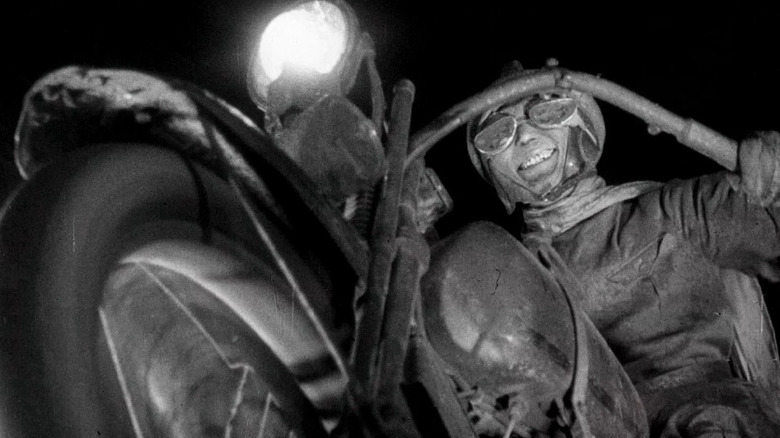

Spies Established All The Tropes You Know And Love (And The Ones You Don't)

There's an early subtitle in Fritz Lang's "Spies" that, depending on the translation, carves the genre down to its very marrow: "Important documents have disappeared!"

The film is as universal as its namesake, though that may have been in self-defense; Lang was forced into making a crowd-pleaser after the financial disaster of his magnum opus, "Metropolis." But in trying to sell popcorn, Lang minted dozens of spy clichés wholesale. A square-jawed man of action known only by his agency number -- 326, in this case. White-knuckle set pieces rolling into each other, with the hero only needing a brush-off between an astounding train crash and an impressive motorcycle chase. The supervillain-as-puppeteer, a goateed vision of evil shrouded in ambiguous smoke.

The only innovation that hasn't been Xeroxed into oblivion is an omniscient focus on the evildoer. Rudolf Klein-Rogge's Haghi is the star of the show. For all it inspired as the spy film primordial, "Spies" shows much more patience for the outlaw and, in the inevitable end, maybe even sympathy.

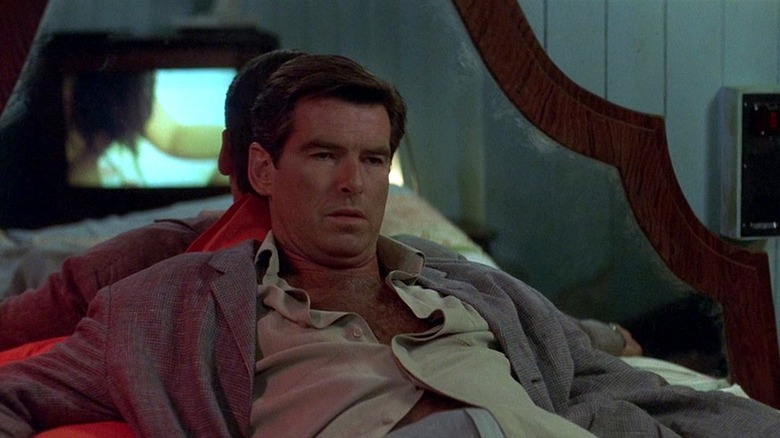

Forget 007, The Tailor Of Panama Is Brosnan's Best Spy Film

James Bond is a fantasy. Andy Osnard is a byproduct, a flesh-and-blood sexual harassment case on Her Majesty's secret service, hiding as far from Her Majesty as diplomatically possible. It's an underappreciated casting coup that Osnard happened to be played by the sitting Bond.

Pierce Brosnan seems more at home with the dirty spycraft of John le Carré than he ever was with Ian Fleming's jet-setting. When Osnard blackmails presidential tailor Harry Pendel (Geoffrey Rush) into feeding him information, it sounds like a timeshare presentation. When he finds out that Pendel is making the intel up, it sounds like a dream -- less work for ol' Andy Osnard if the rumored revolution stumbles before the starting line.

This isn't the most potent dose of le Carré's pencils-down pessimism, where frantic pawns are sacrificed to the strategy of men continents away from the frontlines. Panama isn't a frontline, and Osnard isn't a pawn -- he's just a loser looking for a picturesque place to die.

Mission: Impossible Is Brian De Palma's Masterpiece

First-time producer Tom Cruise met Brian De Palma by accident during a fortuitous dinner at Steven Spielberg's house. That night, he hosted his own 14-hour De Palma film festival.

For "Mission: Impossible," there was no second choice. Among blockbusters, "Mission: Impossible" is the perfect marriage of art and artist. For all the exploding sticks of chewing gum and rubber Jon Voights, De Palma is the handiest gadget of all. He opens the film on one agent (Emilio Estevez) watching another (Cruise) carry out a real interrogation in a fake interrogation room. It's a warning. On a good day, this is a world of illusion. On the rest, it's a place where Three-card Monte dealers try to con each other.

The genuine tricks play straight. Close-up magic with an all-important disc. Hunt catching himself inches above a pressure-sensitive floor. Everything else is machine-tooled to make you feel the clandestine gibberish more than follow it. De Palma knew what he was doing; to date, he considers the one-two punch of "Carlito's Way" and "Mission: Impossible" the pinnacle of his career.

The Hunt For Red October Is Still The Best Tom Clancy Adaptation

Just as President John F. Kennedy unofficially christened Ian Fleming the spymaster-in-chief, so Ronald Reagan anointed Tom Clancy, turning the insurance salesman into a best-selling novelist overnight.

"The Hunt for Red October" is a miracle of economy. It's not short, running 135 minutes from tip to tail. Much of Clancy's tech-manual plotting about "caterpillar drives" and "Crazy Ivans" survives intact. And yet, in the distillation from hardcover doorstop to fifth highest-grossing blockbuster of 1990, it improved. The script from Larry Ferguson and Donald E. Stewart streamlines Clancy's story into one long zoom, starting wide with meetings in the halls of power and ending tight on an accountant trading potshots with a Russian traitor between nuclear missiles.

Director John McTiernan and cinematographer Jan de Bont, reuniting from "Die Hard," weaponize the anamorphic sweep. Early on, when boy scout Alec Baldwin inspects a submarine under construction, nothing has ever looked bigger. By the end, faces loom larger, spelling panic only in wrinkles. No Clancy adaptation yet has matched it. None have had a performance like Sean Connery's, either.

The Bourne Identity Reinvented The Modern Spy Thriller

After "Swingers" and "Go", director Doug Liman wanted to make a James Bond movie but knew he was too green and too American to land the gig. Instead, he turned to an old favorite by Robert Ludlum.

Jason Bourne wakes up with no past, save a few concerningly violent skills. What Bourne he does have, however, is plenty of style. With cinematographer Oliver Wood and a script from soon-to-be franchise steward Tony Gilroy, Liman knocked the genre off its tripod. Every fistfight is a life-or-death struggle, the camera abandoning traditional coverage to dodge punches alongside the hero. Every chase is shot low and close, as if exclusively watched by innocent bystanders and rattled passengers. The effect is aggressive and grounding -- the audience is always as frenzied as the world's most wanted man.

Liman's experimental directing style, requiring four rounds of reshoots, cost him a franchise but earned him a roundabout legacy -- Bond took obvious notes for "Casino Royale."

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Plays A Very Dangerous Game

Espionage is a glorified game of pretend. Just look at the title of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy," strung together from the codenames of an intelligence agency known as "The Circus." These are government employees in their finest tweeds playing chess in a room with all the charm of a microwave oven.

John le Carré's spy games are won on sustained precision -- knowing just as little as the enemy, but maintaining the stiff upper lip until they flinch first. Director Tomas Alfredson channels that agonizing stillness into every scene, and Gary Oldman, taking up the spectacles as le Carré's most famous creation, pushes it even farther.

George Smiley is the ugliest duckling in a department staffed by nothing but, unremarkable to the point of invisibility and seemingly immobile, but endlessly churning underneath. His inquiries land with the impregnable force of an insurance investigator, his silences with the self-destructive courtesy of a priest awaiting confession. What makes Smiley, Oldman's performance, and the film itself an all-timer is his drunkenly revealed philosophy: the only moral difference between him and his quarry is the quaint codename.

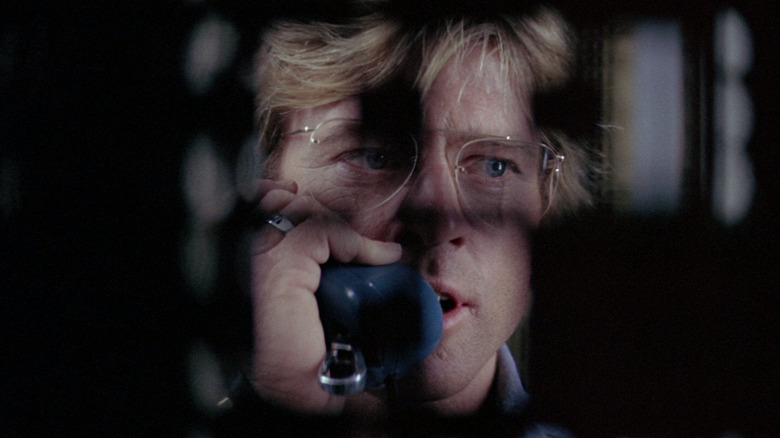

3 Days Of The Condor Is A Twisty Thriller With An Unforgettable Ending

"What is it with you people?" asks unlucky CIA analyst Robert Redford, somewhere near the end of his rope. "You think not getting caught in a lie is the same as telling the truth." It took him long enough to learn.

Joe Turner spends his days poring over paperbacks and doctor's office magazines in the statistically impossible chance they contain coded threats against the American Way. Aflutter with his latest goose chase, Turner picks up lunch. While he's out, the rest of the office is gunned down in a bloody haze.

"3 Days of the Condor," already winnowed down from the original novel's six, is a masterclass of focus. Turner has been dragged into a completely plausible conspiracy. He's the latest pin on a corkboard already tangled with yarn. It's impossible for him to ever see the whole weave. He bluffs that nobody else can either. The ending, almost supernatural in its calm, remains one of the most chilling in spy cinema.

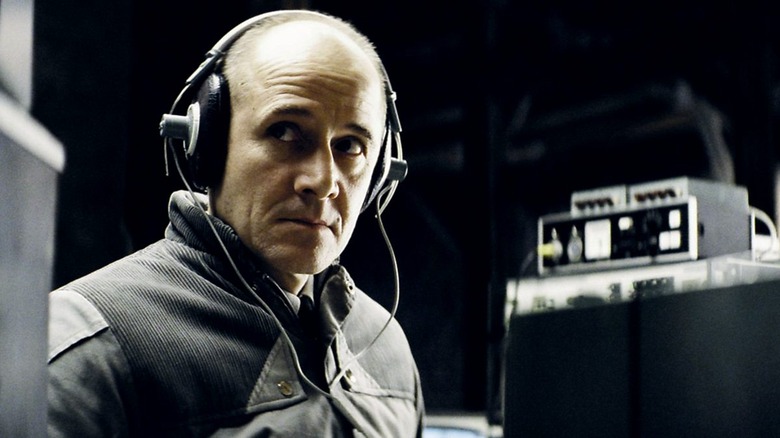

The Lives Of Others Does So Much With So Little

In most dramas about the cloak-and-dagger business, morality is treated as a lost cause. Flags matter more than feelings, even though operators spend most of their careers squinting at the other guys. "The Lives of Others" starts beneath a dark flag -- the German secret police circa 1984 -- and grinds toward the light.

Captain Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühle) didn't write the book on interrogation, but he does teach the class. Human nature is a series of ones and zeroes to him, tells and truths. When he receives an unusual target for surveillance -- renowned playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) -- Wiesler embraces it like any other operation. Bug the apartment. Await incrimination. But all it takes is one whisper of selfish motive from the powers that be to make the eye in the sky question his entire career.

In his feature debut, director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck wrings more suspense out of two rooms than most filmmakers can from the world stage, and wonders if the only difference between peeping toms and guardian angels is who's minding the listening devices.

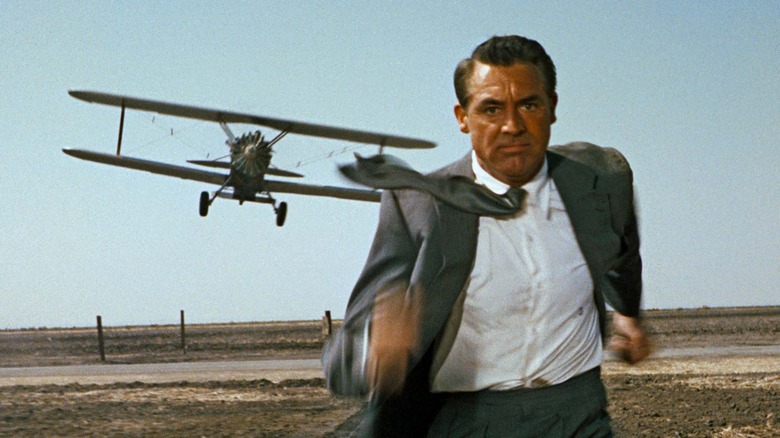

North By Northwest Really Is The Ultimate Hitchcock Film

Screenwriter Ernest Lehman pitched the possibility of "North by Northwest" to its director in the purest way it has ever been described: "The Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures." It started as a disparate collection of doodles the legendary filmmaker couldn't fit anywhere else. A murder at the United Nations. A foot chase across Mount Rushmore. This creative process would become SOP for blockbusters -- it's how each "Mission: Impossible" is made -- but was unheard of at the time.

New York ad man Roger Thornhill, dangerous only in charm, is mistaken for George Kaplan, somebody dangerous enough for very powerful people to want him dead. Seeing no way out but through, Thornhill decides to scour the country for the real Kaplan to prove his innocence. His foolhardy crusade leaves him framed for the murder of a foreign dignitary, accosted by a crop duster, and dangling off a former president's face.

What holds "North by Northwest" together are the combined star powers of Cary Grant and Eve Saint Marie, beautiful people in beautiful peril. Anyone too concerned about the grinding of gears is given one of cinema's finest kiss-offs -- all unnecessary exposition is drowned out by an airplane engine.

The Ipcress File Presents A Gritter, Grounded Alternative To Bond

Just six months after "Goldfinger" and nine before "Thunderball," James Bond co-producer Harry Saltzman put out a much less exotic alternative for audiences burned out on ejector seats and high adventure. Harry Palmer, unnamed in Len Deighton's novels, longs for even low adventure. Fresh-ground coffee is his only vice. A good day at work means as little interaction with his superiors, all animatronic parodies of British heroism, as possible. Fresh air comes with a friendly reminder that he's just the office drone with the most exploitable criminal record.

As Palmer, Michael Caine takes it all like paid detention, the famed Curry & Paxton frames turning his half-awake eyes into cocky little security cameras. He doesn't think he'll get away with anything -- he never has -- but he knows his mission about the mysteriously reappearing scientists will get worse in ways he hasn't even begun to understand. Naturally, nightmarishly, it does.

All three of the theatrical Palmer films are worth seeking out. "Funeral in Berlin," directed by fellow Bond alum Guy Hamilton, is the nittiest and grittiest. "Billion Dollar Brain," a sore-thumb project for firebrand Ken Russell, goes disturbingly gonzo. But "Ipcress," shot alternately like a stakeout and hypnosis by Sydney J. Furie and cinematographer Otto Heller, remains the best of the bunch.

From Russia With Love Is The Purest Expression Of Ian Fleming's 007 Yet

24 Bond missions later and counting, "From Russia With Love" still tops best-of lists and endures as shorthand, often by the latest creatives to take the reins, for what the world's greatest secret agent could and should be. Watched today, it's a franchise urtext, with whole characters, sequences, and subplots borrowed, budgeted up, and done over again, if rarely so well.

"From Russia With Love" traded the tropical seclusion of "Dr. No" for a European travelogue. Bond would be waging the Cold War in the trenches, with evil conglomerate SPECTRE taking the geopolitical hit. All 007 has to do is help a Russian defect with her side's bespoke decoding device. There is no threat of global domination or destruction. The most lavish gadget is a briefcase with pocket change sewn into the lining. The villains want nothing more than the untimely demise of James Bond. James Bond wants nothing more than the decoder and the conspicuously beautiful defector. This is spycraft built for speed, suspense, and shameless sex, as Fleming intended.

"From Russia With Love" turned James Bond from a fluke -- adjusted for inflation, "Dr. No" cost less than 4% of the estimated $250 million spent on "No Time to Die" -- to a franchise. "Goldfinger" brought in the pomp and circumstance the very next year. It's a matter of personal taste as to which film laid the superior groundwork, but the case could be made that neither has been surpassed since.

Spy Films Don't Get Better Than The Spy Who Came In From The Cold

This would qualify for the gold by a monologue alone. It arrives late, at the exhausted end of an explanation. In a moment of self-loathing clarity, Richard Burton's Alec Leamas lays plain the entire Cold War to a companion not used to the same questions -- do the letters you work for spell f-r-i-e-n-d -- or the numb answers: today they do.

John le Carré's definition of "spy" is right up front: "They're a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me..."

In cinematographer Oswald Morris's bleak black-and-white, only ruin shows correctly. The remains of Berlin. The crumble of a prison cell. The bags beneath Burton's eyes. Beauty muddles -- a lakefront postcard view is just gray-on-gray. Leamas has kept his nose to the cobblestones too long to notice anyways. Director Martin Ritt gives him precious little chance to see anything else. Espionage here is an endless game of chicken, played until nerves are shot and, past that, bars stop serving. The only action is reaction. Leamas violates that golden rule only once, at the very end. It's the closest thing a seedy, squalid bastard like him gets to job satisfaction.

Read this next: Who Are The Top 15 Best Movie Spies?

The post The 15 best spy movies of all time appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/3gubD0k

No comments: