Clint Eastwood's 14 Best Roles Ranked

In "Adventures in the Screen Trade," screenwriter William Goldman cites the Quigley poll, which asked theater owners to list the most bankable actors and actresses in the business, as proof that stardom is fleeting. The top 10 money-making stars of 1971 share only one name with the 1981 ranking: Clint Eastwood, still in second place a decade later.

In Goldman's belated follow-up, "Which Lie Did I Tell?," he repeats this exception again because, miraculously, Goldman and Eastwood worked together 15 years after his first assessment. In between, Eastwood topped the list three times.

Eastwood has been an anomaly since his very first performance, when an English teacher cast him in a play specifically because he didn't want to act. Asked about his longevity in 1977, then only on the fourth of his 39 films behind the camera, he dodged with deprecation: "I don't have a lot of brains, but I got a good gut." It takes more than that to become legend, a monument to the aging New West in the way his most indelible characters were to the Old. In a review of "Pale Rider," Roger Ebert put it as plainly as the man would appreciate, if grander than he'd ever accept: "No actor is more aware of his own instruments." Here are 14 of Eastwood's finest symphonies to prove it.

Frank Horrigan — In The Line Of Fire

Eastwood was 10 years past the mandatory retirement age when he played Secret Service agent Frank Horrigan. The extra mileage works in his favor here -- this 62-year-old 50-something has been through hell.

Infamy does that, especially when the infamous party happens to have the worst case of butterfingers in contemporary American history. Horrigan was jogging beside the Lincoln Continental on that hot day in Dallas when Lee Harvey Oswald shot John F. Kennedy dead. That makes the emergence of a new would-be assassin more than just the job description -- it's divine intervention.

Eastwood runs, jumps, and falls down with uncommon valor, but it's his hair-trigger instability that makes the difference. When he explains why he didn't run for the president so many decades ago, it sounds like a eulogy for his younger self: "I just couldn't believe it." His obsession teeters on the deranged; this man is itching for one last chance to catch that bullet. So was Eastwood -- this remains the last film Eastwood worked on exclusively as a gun-for-hire, his creative involvement limited to recommending director Wolfgang Petersen.

Jonathan Hemlock — The Eiger Sanction

In 1967, when Sean Connery first stepped away from the role, Clint Eastwood was offered James Bond. He declined based on his lacking the proper accent. Eight years later, he wouldn't need one.

As a novel, "The Eiger Sanction" operated as direct Bond parody. As a film, it's played terminally straight. Exaggerations and caricatures become flesh and blood punchlines -- the first 30 minutes now play like a speed-run of problematic content. Eastwood's Jonathan Hemlock, a spy in active retirement as an art professor, leads the flimsiest double life since Superman. Eastwood would figure out Clark Kent later, as a master thief-cum-artist in "Absolute Power -- this one's all about the birds and the planes.

It's really Eastwood up there, scaling the Alps, doing what no Bond had done before. That commitment alone would earn it a place as his most physically daring work, but "Eiger" offers an even rarer treat: Eastwood at his most continental.

Wes Block — Tightrope

Just eight months after his fourth outing as Harry Callahan, Eastwood played another cop with a less crowd-pleasing vice in "Tightrope."

Wes Block spends his mornings corralling his rambunctious daughters and his nights testing the waters of BDSM. Every time he walks into a brothel for questioning, Block shows his appreciation for the patronage. Putting him on the case of a serial killer copying his kink is like sending Jekyll after Hyde, though it's tough to tell the difference by strip club strobe lights.

"Tightrope," ghost-directed by Eastwood, is his most sexual work on either side of the camera. As star, he writhes, naked and greasy, atop his latest anonymous conquest, who only had to wink at him. As filmmaker, he keeps the camera rolling long past the point where you'd cut for network television. The most squeamish scene, in which Block flinches at the possibility of sex with a woman he actually cares about, isn't blue at all. Given Eastwood's radioactive personal life, it all begs closer examination, but without any subtext it's still a one-of-a-kind performance in an overlooked thriller.

John McBurney — The Beguiled

As often as he's immortalized bad men doing their best, Eastwood has only played a truly unrepentant bastard once, the same year that "Dirty Harry" ensured he never would again.

Corporal John McBurney topples into "The Beguiled" as a Union soldier more dead than alive. His first conscious act is kissing a 12-year-old girl. Is it to keep her quiet as a Confederate patrol passes, or is McBurney just that despicable? Psychosexual nausea clings to the picturesque Louisiana scenery like so much Spanish moss, but one thing becomes absolutely clear: John McBurney is the male ego on crutches, kept alive by the guile in his veins and the rage in his arteries.

By the time his bandages come off, revealing Eastwood at his most beautiful, he's a bed-hopping Machiavelli. Even his requested nickname -- McBee -- sounds like a candy-coated con, better suited for a teddy bear than a strange man holed up in a finishing school. When his mask slips, Dirty Harry disappears entirely behind bug eyes and sweat shine, calling his caretakers everything but "ma'am." It's a shame Eastwood never turned full heel again. He's great to hate.

Red Stovall — Honkytonk Man

"Honkytonk Man" almost disappeared in the shadow of more crowd-pleasing projects, the effects-heavy "Firefox" and a fourth Dirty Harry movie, but that's almost the point. It's a funeral for a breed of folk hero that not many noticed dying.

Red Stovall's religion is country music, and dive bars are his church. He's the rare sinner who knows what Heaven looks like: the Grand Ole Opry. An unlikely opportunity to play that hallowed stage is Red's last chance at an afterlife, if tuberculosis doesn't claim him first.

Eastwood sings. His voice is already suited for caterwauling, but he rends it older. Even in his glories, he sounds like broken glass pieced back together. The decline is obvious to his nephew, played by actual son Kyle Eastwood, but baffling. The boy sees a dying light, but not the darkness. The bond between the two is bittersweet poetry -- the kid just wants the old man to live, but the old man wants to live forever. With any luck, he'll never understand the difference.

Thunderbolt — Thunderbolt And Lightfoot

"Thunderbolt and Lightfoot" is neither fish nor fowl. It's not quite a capital-E Eastwood picture (he plays anywhere from second to fourth fiddle depending on the scene) and not quite a '70s crime thriller -- the climactic heist puts Jeff Bridges in Bugs Bunny drag. That eccentricity enticed the star in the first place; Eastwood was so enamored with Michael Cimino's script that he let Cimino use it for his directorial debut.

The distance works. Clint's Thunderbolt is a man apart and alone, even among co-conspirators. The thief's alias as a small-town preacher is the kind of mythology that doesn't often leave Eastwood's frontier; this is a man intimately acquainted with death. It takes Lightfoot, Jeff Bridges as indestructible youth incarnate, to lighten him up. The two eventually get into an expected caper, but that's all busywork.

This is a love story. Just watch the way Eastwood puts up a giggled fight when Bridges tries to smear raccoon feces on him while driving. The bond won Eastwood's highest honor: When his younger co-star wanted to experiment, the take-averse star relented with his own brand of affection: "Give the kid a shot."

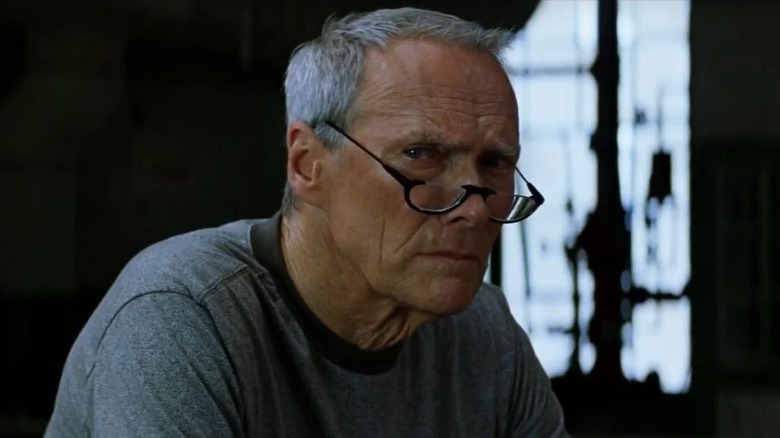

Frankie Dunn — Million Dollar Baby

In 2003, on the interview trail for "Mystic River," Eastwood warned of his retirement from acting: "The end may come sooner than you think." The following year, he found the blueprint for every role he's played since.

Frankie Dunn has the kindness and complexion of a Brillo pad. He moves like a tectonic plate and, when his mouth is open, you can hear the grinding. Whatever Frankie is, he's been that way too long to be much else. With any luck, he has enough time left for one good decision, and none of Eastwood's late period loners get a tougher lose-lose than Frank the washed-out boxing trainer.

In "Blood Work," Eastwood's previous turn, he was doing his best Dirty Harry, still a leading man. "Baby" stands tall as his last phase change. Eastwood wasn't getting old anymore; he'd made it. He's not just a man but an American legend made suddenly, obviously mortal. The difference is never clearer than when he threatens a priest trying to give him answers: "She's not asking for God's help -- she's asking for mine." Not long ago, it would've sounded scary. Here, it only sounds scared.

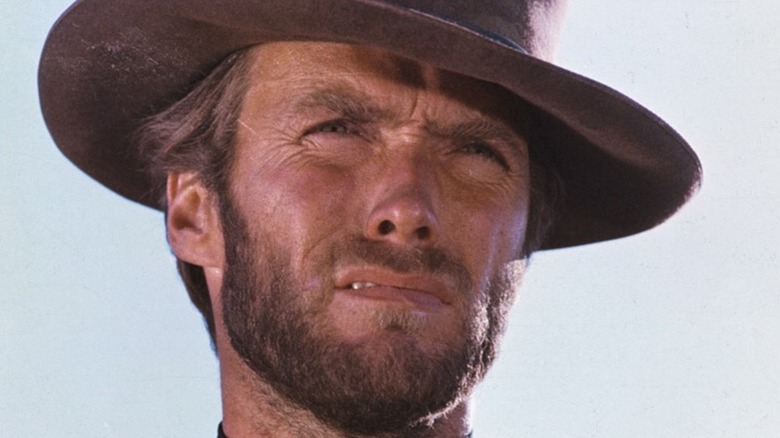

Blondie — The Good, The Bad And The Ugly

There are two competing images of the cinematic West. One is John Wayne in any given Stetson. The other is more specific: Not just Clint Eastwood, but Clint Eastwood as the Man with No Name.

In "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly," he gets his most enduring nickname, "Blondie," and something like morality -- the titular "Good." In the crossfire of the Civil War, it's all relative; He makes a living repeatedly cashing in his fugitive accomplice and springing him when the reward clears. What sets Blondie apart from the other two rogues after $200,000 worth of Confederate gold is mercy, however slim. A smoke for a dying man. A parting shot for a dead man walking. Beneath his Naugahyde and steel lies a code. Ask him about it and he'd probably kill you. Talk is cheap for the Man with No Name, and he's only a day's ride away from rich.

This is cinematic myth, impossible to oversell, incapable of disappointing. By the end, Eastwood's a monolith, his face fit for Mount Rushmore's Spanish double. He's already most of the way there upon arrival. With a puff of cigar and holler of Ennio Morricone's legendary score, Eastwood enters, immortal.

The Stranger — High Plains Drifter

The devil rides down from the mountain. The town of Lago makes a deal. They get exactly what they bargained for. That nameless drifter may just be a mortal out for fraternal vengeance. Then again, maybe the helpless locals deserve everything they've got coming.

His character, only known as unknown, materializes out of the horizon heat. On the first afternoon, he kills three men over a shave and rapes a woman on a whim. When the startled townsfolk enlist him to fend off the murderers en route, he empowers their downtrodden and strongarms their prejudices. His nightmares are the only hints at his humanity, replaying a violent death that may or may not be his own. In early drafts, he was explicitly mortal, but Eastwood wisely reconsidered.

It remains Eastwood's most cryptic role; even "Pale Rider," the angelic half of this rhyming couplet, is less ambiguous. His performance is bleaker without life or lore. The devil may live in Hell, but the Stranger builds it in his own image and burns it to the ground.

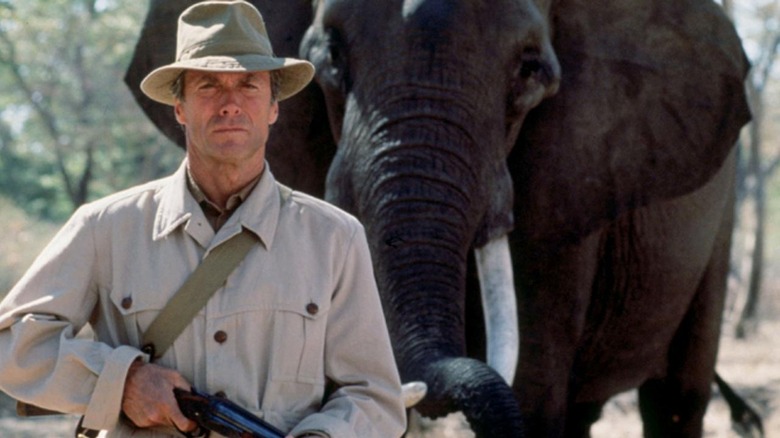

John Wilson — White Hunter Black Heart

Eastwood has never gussied up his instincts as a filmmaker -- "Things would just pop up and I'd get a feeling about them." In this, his most underrated performance, he stretches that compulsion to self-destructive extremes.

John Wilson, a barely veiled analogue for John Huston, is headed to the Congo to direct his next picture, a barely veiled analogue for "The African Queen." Not that he can remember the title anyways. Wilson didn't sign on for the art or to ease his crippling debt. He signed on to hunt an elephant, which he calls "the only sin you can buy a license for and then go out and commit."

As pseudo-Huston, Eastwood ties himself in an erudite knot, his trademark rasp replaced with a social club sing-along, cheroot cigars with vestigial cigarillos. For a star minted on iconic minimalism, it's a daringly complete performance. He telegraphs any discomfort as the filmmaker's own self-loathing. Such is the contradictory plight of a man's man in decline, renowned only for making pretty people play pretend. Does he direct to play God, or is that just the job description? Wilson can't answer. He's too busy dazzling his phony tablemates with tales of derring-do.

Josey Wales — The Outlaw Josey Wales

The Eastwood legend was firmly established with Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy. Ten years after "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly," he held that legend at gunpoint and demanded answers. How does the Man with No Name lose everything but his cool?

Pain and hate, mostly. The Civil War costs border-state farmer Josey Wales his family. Misplaced trust in his similarly enraged countrymen costs him a cause. His infamy is an accident that he's quick enough on the draw to justify. All Josey has to his name are four revolvers and a $5,000 bounty. All he can afford to do is run. The assorted misfits who happen to be running in the same direction? Well, that's their prerogative.

Eastwood has explored the surrogate family several times since, most explicitly in the underseen "Bronco Billy," but never more humanely. Cherokee. Navajo. Widows. Orphans. A shabby harbinger of death. All they have in common is the misery that abandoned them together. In a world this hard, that's as good as blood. Early on, Josey says this to terrorize, but eventually it sounds like a one-man peace treaty: "Dyin' ain't much of a livin', boy."

Robert Kincaid — The Bridges Of Madison County

Kincaid is a romantic, an artist, an ambassador of the world. His National Geographic photographer offers a hint to what lies beyond the county limits. For all its flowered sprawl, Iowa feels like four walls without a roof; even the bridges are more constricted than they need to be. To lonely housewife Francesca Johnson, the kindly stranger in the GMC pickup is the handsome sum of her every what if.

Clint Eastwood shouldn't speak Hallmark, and yet lines like, "I don't want to need you," only sound truer for his resistance. Meryl Streep acts at an entirely different pitch, and yet Eastwood recruited her personally for the role. There's no arguing the magnetism between them. It's as invisible as the "personal comment" Kincaid's editors prohibit in his photos. Eastwood lets it be, trading strong silence for soft, like a warm smile fading in the rain. 40 years after his big screen debut, Eastwood could still surprise.

Harry Callahan — Dirty Harry

No role has deeper cemented the public image of Clint Eastwood than "Dirty" Harry Callahan. Irresponsible violence. Hushed bravado. Right wing. Big gun. But as the prototypical "loose cannon," Harry isn't that loose. His most infamous tactics -- skipping Miranda rights and playing .44-caliber roulette with cornered perps -- abide an unwritten constitution. The script's original title doubles as the cardinal rule: "Dead Right."

But he isn't. Harry's law gets a serial killer released from custody, a busload of children kidnapped, and his partner wounded. For all his friction with bureaucracy, the brass is right -- Dirty Harry is about as dangerous to the average San Franciscan as his latest suspect. Even director Don Siegel was on their side: "What my liberal friends did not grasp was that the cop is just as evil in his way as the sniper."

While watching Eastwood taunt his prey like a slasher villain in brown tweed, it's hard to disagree. Sequels, all made in defiance of the oft-forgotten closing seconds, colored Harry human to mixed results. "Magnum Force" provides a carnival mirror reflection to shoot at, and "Sudden Impact" does the same for the killer, but they all miss the same point as the parodies. When Dirty Harry asks if the punk at the end of his Magnum feels lucky, he does it with a smile.

Will Munny — Unforgiven

Will Munny is Clint Eastwood's best role for the simple reason that nobody else could've played him, not even a 10-years-younger Clint Eastwood; the David Webb Peoples script gathered dust in his desk for a simple reason: "I thought I should do some other things first."

The weight of other things drives scrimshaw history into Eastwood's cheeks and his temples, all branching from the trademark squint that registers more like pain than it used to. Munny is an antique content to rust. The New West needs pig farmers, not drunken murderers fashioned into folk heroes by wanted poster and paperback. Faced with a big enough bounty, though, any man's liable to take his rifle off the wall.

Without Eastwood, Munny's a clown. He can't ride. He can't shoot. It's still amusing, but the audience knows better. His transformation back into a notorious monster is slow and agonizing. The shootouts are bloody and unsatisfying. There are no white hats or black hats, just scoundrels at cross-purposes. Regret hangs like a noose perpetually out of frame, and only Munny seems to notice it. That's the trick; violence's reward isn't a book deal, a bad reputation, or a brutal end. It's living with it. If Eastwood hadn't come back to "Cry Macho" after doing "some other things first," this would've been Eastwood's last close-up in a cowboy hat. Sunsets don't get much better.

Read this next: 5 Clint Eastwood Westerns To Watch After Cry Macho

The post Clint Eastwood's 14 Best Roles Ranked appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/3nDOk8G

No comments: